World War I was a prolonged, brutal, and costly conflict; and was followed by a virulent pandemic which killed even more people – estimates vary from 50 to 70 million worldwide.

Beyond the days immediately following the Armistice, there was little cause for celebration. The hangover would persist.

In 1921 Torquay had a population of 39,431. All were affected by those two seismic events in a time of grief, social change and the end of certainties.

The real ongoing consequence for Torquay was, as the historian Correlli Barnett argues, that the conflagration, “crippled the British psychologically “.

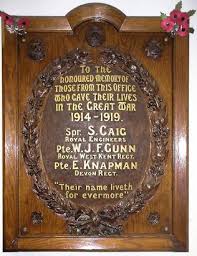

The physical manifestations of mourning could be viewed in the town’s workplaces and in private shrines in so many homes. Remembering was rightly manifest and central in the building of monuments to the Fallen, the most notable being Blomfield’s 1920 War Memorial in Princess Gardens. Few would not have known a friend or family member among the 609 named there. And everywhere those broken in body and mind could be seen in Torquay’s streets.

Torquay’s churches and chapels commemorated the Fallen but this time of mass grieving also revitalised Spiritualism. Across town séances were held to contact that other shore. Sherlock Holmes author Conan Doyle proclaimed his belief in the afterlife on August 5 1920 in a lecture entitled ‘Death and the Hereafter’ at Torquay Town Hall. The meeting was presided over by local builder and Freemason Henry Paul Rabbich, the then President of Paignton Spiritualist Society. Notably, the audience was mainly female.

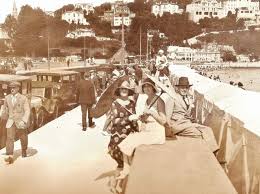

As Torquay entered the ‘Roaring Twenties’, it steadily became evident that this would be a decade of contrasting and polarising experiences. The ‘Bright Young Things’, those born after the turn of the century and with the privilege of wealth, had a good life in a party town, freed from the restrictions their parents experienced. Though perhaps they lived with a sense of guilt and reacted with a life of hedonism.

Conversely, those returning from Flanders, expecting the ‘land fit for heroes’ promised by Lloyd George, were to be disappointed. Wages were being cut as the country had lost overseas markets and faced growing competition, particularly from the USA and Japan. Many would face a period of unemployment, deflation and economic decline. By the mid 1920s unemployment had risen to over 2 million. This would lead to political upheavals and some to the superficial attractions of Mussolini’s fascism.

All faced a decade of disorientation. Social relationships which had taken a century to build up were being dismantled, creating a modern Torquay so different to that of the Victorians. Indeed, some historians see 1914 as the real end of the Long Nineteenth Century, the conclusion of a British Belle Époque. From then on, so many convictions and accepted truths would inevitably crumble.

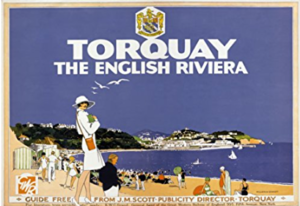

Torquay had always focused on attracting the upper class visitor. However, the elite had taken the greatest proportional hit during the War. There were far fewer confident and educated sons of privilege around. In a symptom of social change Torquay’s much anticipated opera house would never be completed.

Conscription had eroded traditional class distinctions and self-regulating deference. Families had grown to like earning wages in factories while new advances in technology reduced the need for a large local servile class.

The 1920s were particularly liberating for women. During the War many women had been employed, giving them a wage and a degree of independence. Women over 30 gained the vote in 1918, and by 1928 this had been extended to all women over the age of 21. This was reflected in new fashions -shorter hair and shorter dresses, while women started to smoke, drink and drive motorcars. The ‘flapper’ appeared, perplexing a staid seaside society.

The long-accepted hierarchies of class and gender were rapidly decaying.

The English Riviera image presupposed Torquay as an international town, though it further saw itself as a product of the imperial mission. Yet, in the post-War period the Empire was fraying and the treasured family of nations beginning to dissolve.

The nation’s oldest colony had already decided on divorce. In Ireland nationalists fought a brutal civil war from 1919 to 1921 which British paramilitary forces, the ‘black and tans’, responded with violence. The Anglo-Irish Peace treaty created an Irish free state but six northern counties partitioned off to remained part of the United Kingdom. This represented a territorial loss for Britain that was equal to the loss sustained by Germany in 1919. The debates over Irish Home Rule had divided Torquay’s politics for decades.

Further afield participation in the War appealed to a growing sense of nationalism. Many recognised that it would be only a matter of time before the Empire was dismantled entirely.

The early Twenties were a time of melancholy and sorrow; but also carousing and emancipation. Torquay would spend those years deciding its place in a greatly changed world.

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us