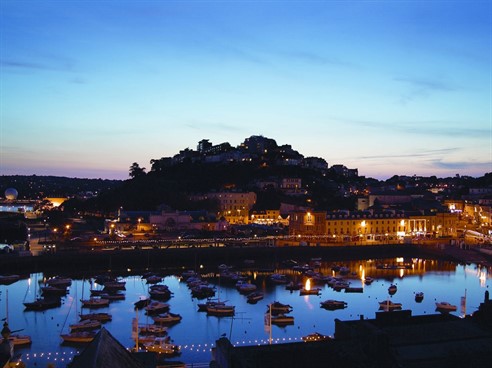

There were more ‘hard drugs’ in Torquay in the nineteenth century than any time before or since.

An estimated 5 out of 6 working class families used opium on a regular basis in Victorian England, and many of Torquay’s famous residents and visitors freely used a variety of drugs that are illegal today.

Opium was primarily imported into Britain from Turkey and India with an estimated 22,000 pounds of opium being brought into the country in 1830 alone. There were also attempts made to grow opium in Britain as an “agricultural improvement.” As importation increased, opium became the standard medication for almost everything – the Victorian version of aspirin. Many patent opium products appeared and physicians dispensed opiates directly to patients or wrote prescriptions for them.

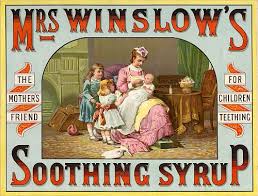

Numerous household remedies contained opium, including many directed at children. Thomas DeQuincey, the author of ‘Confessions of an English Opium-Eater’ called opium ‘God’s own medicine’. Across chemist counters could be bought treatments such as Dalby’s Carminative, McMunn’s Elixir, Batley’s Sedative Solution, Mother Bailey’s Quieting Syrup, Dover’s Powder, and Syrup of Poppies. Godfrey’s Cordial was sold by the thousands of bottles and was commonly administered to children and infants to help them sleep.

They were easily obtained. Visiting a chemists shop in a small town comparable to Torquay, a physician wrote: “Anyone who… strolls about the streets on a Saturday evening, watching the country people as they do their marketing, may soon satisfy himself that the crowds in the chemists’ shops come for opium; and they have a peculiar way of getting it. They go in, lay down their money, and receive the opium pills in exchange without saying a word. For instance… one evening in August 1871; went into a chemist’s shop; laid a penny on the counter. The chemist said – “The best?” I nodded. He gave me a pill box and took up the penny; and so the purchase was completed without my having uttered a syllable. You offer money, and get opium as a matter of course. This may show how familiar the custom is…”

Understandably, opium was utlised for recreational as well as for healing purposes. Injecting, however, was seen as being generally unacceptable. Though there were opium dens in London and many ports catering to seafarers, smoking was also seen as a vice practiced by ‘Orientals’. It’s therefore unlikely that Torquay had the kind of opium den seen described in the literature of the time.

Rather, the use of mood altering substances was generally through liquid intake in the form of laudanum and absinthe.Laudanum was a combination of opium and alcohol. It was used in ancient Greece and has been a pain killer and mood altering drug for centuries. Until the early twentieth century, laudanum was sold without a prescription and was a constituent of many medicines.

Initially it was seen as a lower class drug, but later became popular among all social groups. Wealthy women even used laudanum as a fashion aid in order to achieve the desirable pallid complexion of tuberculosis. It was less expensive than alcohol because it wasn’t taxed. DeQuincey wrote of how you could purchase laudanum from many street vendors: “Happiness can be bought for a penny”. In comparison, beer cost slightly more than a penny a pint in the 1880s. Of course, laudanum was highly addictive.

Absinthe is an anise-flavoured spirit, high in alcoholic content. Although a range of herbs were used in making absinthe, wormwood was an important ingredient. Used to eliminate tapeworm in humans, it had the side effect of a mood altering drug. Yet, it was relatively expensive and its use was restricted to the middle class and the artistic community. Being very bitter, absinthe was usually diluted with water and with sugar. The absinthe was placed in a glass and water was drizzled over a sugar cube. One way to consume laudanum was by adding a few drops to a glass of absinthe, as Johnny Depp is seen doing in the Jack the Ripper movie ‘From Hell’.

We have numerous records of famous users of opium. Indeed, it appears as though all of the Romantic poets, with the exception of William Wordsworth, used it at some point, often with the objective of enhancing their prose. South Devon visitors that we know used opium are many, and include Percy Shelley in Torquay (pictured below) and John Keats in Teignmouth. Other visitors to the Bay have written well-informed literature describing opium use and there have been suggestions that they may well have been users themselves. Oscar Wilde (who lived in Babbacombe for four months in 1892) featured the drug as part of the decadent life-style described in ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’. Both Charles Dickens and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle described scenes of abuse, the latter featuring the detective Sherlock Holmes.

It seems that only later in Victorian England did people realise that laudanum use was habit forming and that it demanded increasing doses to provide relief. For example, poet Elizabeth Barratt Browning who lived on Torquay Harbourside (and pictured below) was a long term user of opium. She began her use of the drug when she was fifteen to treat the pain from a spinal injury complicated by “nervous hysteria”. She wrote: “My opium comes in to keep the pulse from fluttering and fainting…to give the right composure and point of balance to the nervous system. I don’t take it for ‘my spirits’ in the usual sense; you must not think such a thing.”

Other drugs were locally available. An interest in hashish came from a growth of interest in the Orient, though it was apparently confined to a small group of prosperous initiates. There is speculation that another Torquay visitor, Alfred Lord Tennyson, was describing the consumption of hashish in his 1838 poem ‘The Lotus Eaters’, for example.

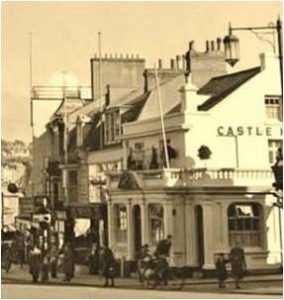

As it is today, alcohol was the most common drug in Torquay – that’s the Castle pictured above, still going since its opening in 1837. Its consumption was a popular pastime, with beer, cider and spirits being given freely to anyone who could afford to buy. This included children of any age. However, drunkenness, and the related loss of self-control, was associated with the lower classes and a real cause for social concern. Along with the condemnation of ongoing disorder in and around Torquay’s pubs and beer houses, alcohol was linked with riots in the town in 1847, 1867 and 1888.

In response, a Torquay Temperance Society was started in 1843. This was set up to take the place of “a Society in which entire abstinence was not a necessary qualification for membership…” (Incidentally, the term teetotal probably comes from the T in total, with some activists signing a ‘T’ after their name to signify a pledge for total abstinence.)

As the working classes were seen as most open to temptation and the greatest threat to public order, a series of British Workman Public Houses were opened “where refreshments of all kinds can be had, but no intoxicating liquors”. The first was in Union Street in 1872, followed by Vaughan Parade – “for the benefit of fishermen and sailors” – and then Market Street. Pictured above is one of Torquay’s alcohol-free public houses.

In contrast, opium use didn’t produce as much social concern. It seems as though the better classes could engage in substance misuse without it being considered much of a problem. If, however, use was taken to excess, it became a vice. Until then, the medicinal use of opiates was respectable and ‘social’ use was tolerated. Indeed, opium was actually preferred because it didn’t produce the violence associated with alcohol. There’s even some evidence that it was quite acceptable for teetotal ladies to use opiates instead of alcohol.