This one is about the secret language of Torquay’s promenading parasol.

First, a definition.

A parasol is not an umbrella. A parasol shades users from the sun; while an umbrella protects the user from rain. But in Victorian Torquay their use was also about social class and gender. Using an umbrella gave a clear indication that a woman could not own or hire a carriage if it was raining. On the other hand, in fine weather a woman with a parasol was a lady who could afford to travel in a carriage; the driver would have to put down the top so the parasol could be used.

The Victorians admired a fair complexion and saw it as a sign of beauty and wealth and a parasol’s stated purpose was to protect delicate skin from the ravages of the sun. From this practical use, the parasol inevitably became an item of fashion and acquired a power far beyond its practical utility.

As with other fashion styles, conspicuous consumption was immediately obvious to the onlooker and ownership was important for local women. The affluent Torquay visitor and resident would own one for each outfit; while middle class or poorer ladies strived to own a minimum of two parasols- one in white and the other in black silk. A poor Ellacombe servant girl might have a simple parasol for church, or for a Sunday afternoon stroll.

During the early Victorian period they were plain, simple, and heavy. But in 1852 Samuel Fox designed the ribbed umbrella, using up stocks bought for making corsets. Alloy ribs made parasols lighter, sturdier and more flexible and by mid-century they came in different colours, often decorated to match dresses, were available in materials like brushed chiffon, and ornamented with tassels, lace and frills.  The parasol found an important role in nineteenth century Torquay as it was the perfect complement to a system of social display, the promenade. It was Charles II who began the promenade by opening up the Mall in order to socialise with members of ‘polite society’. This made it fashionable to stroll along shady walks surrounded by beautiful scenery.

The parasol found an important role in nineteenth century Torquay as it was the perfect complement to a system of social display, the promenade. It was Charles II who began the promenade by opening up the Mall in order to socialise with members of ‘polite society’. This made it fashionable to stroll along shady walks surrounded by beautiful scenery.

It could be argued that the seaside ritual made the town it is today as the practice transferred perfectly to the new coastal resorts. In ‘Persuasion’ Jane Austen described how promenading in Lyme Regis was ostensibly about getting fresh air and exercise, though it was also an excuse for high society to mingle and show off. This was exhibitionism masquerading as healthy living that proved that the participants need not work, could stay at grand hotels, attend the theatre, and wear the latest fashions.

The Alphington Ponies in Torquay

The promenade fashioned the Torquay we know today in parallel with the town’s evolution. The town’s promenading began when Sir Lawrence Palk provided the first pleasure ground in Torwood Street, now known as Torwood Gardens. This provided a well-sheltered meeting ground away from the sea front. It was, however, a private space, an adjunct to neighbouring middle class housing, with annual subscriptions being paid to Sir Lawrence through a private committee and used for the ground’s upkeep.

In 1850 White described the grounds “comprising about 4 acres of land, lately appropriated by the lord of the manor to the use of the public, and are tastefully planted and laid out with gravel walks, forming a sheltered promenade”. At that time the Public Gardens were still in private hands, but in 1853 Torquay’s Local Board took possession for the free benefit of all.

A further promenading opportunity came in 1867 when work commenced on the construction of the outer harbour wall – Haldon Pier. This served as a promenade for those who could afford to pay the entry fee. Torquay’s first seafront garden, Cary Green, was also available as a triangular area complete with a patriotic display of a Sebastopol gun and a flagpole.

The main development, however, was the construction of a new promenade alongside the Torbay Road, together with a new quay wall designed to run between the proposed new pier and the harbour. This allowed the reclamation of three acres of land for a new garden giving the town a long level promenade, or esplanade, where visitors and locals could be ‘seen’ by society. By this time resorts were intensely competitive and were trying to offer the best amenities to potential visitors.

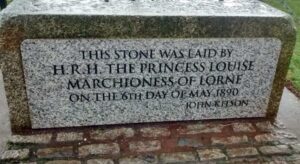

Princess Louise, Queen Victoria’s daughter, laid the foundation stone for the gardens on May 6th, 1890, named Princess Gardens in her honour. And we have an 1859 image of Queen Victoria and John Brown, alongside Princess Louise with parasol.

The parasol was the ideal accoutrement for the Torquay promenade. As noted, while the parasol was necessary to protect ladies from the (occasional) heat of the sun, they did have other purposes. Victorian Torquay was a highly regulated society with limited opportunities for interaction between men and women. There were strict codes of behaviour. When introducing a gentleman and a woman, for example, the gentleman needed to always be introduced to the lady and never the other way around, and never without asking the lady for her permission first.

There were real dangers in losing one’s reputation. Even a slight rumour could irrevocably harm future marriage prospects and affect an entire family. One specific danger was to become known as a coquette, a woman who insincerely acts to gain the attention and admiration of men. There was consequently a real fear of any kind of embarrassment, either from seeming too forward, uncouth, or of being publicly rejected.

This was particularly problematic in a high-class resort Torquay which acquired of a reputation for being a place to meet future marriage partners. It claimed to be the richest town in England and there were certainly plenty of rich young potential candidates. The difficulty was that, unlike promenading at home, other participants were likely to be strangers while families may only be in the resort for a few weeks. Accordingly, approaches needed to be made relatively swiftly. A further challenge was that it was deemed inappropriate for a woman to walk alone and so all were chaperoned, usually by a male relative.

In an era when people often had to communicate without words, less overt signals of intentions and feelings then needed to be made. Hence, systems of subtle messaging evolved between women and men. Indoors, this could be accomplished by using a fan, gloves or a handkerchief. Outdoors, and on Torquay’s promenade, the parasol could be utilised discretely to flirt in an acceptable way.

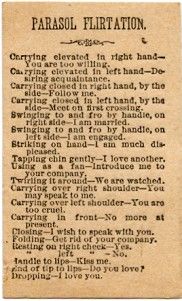

We know this as numerous books were written that gave standardised parasol signals. These included the following:

• Carrying it closed in the left hand: “Meet on the first crossing”

• Carrying it closed in the right hand by the side: “Follow me”

• Closing it up: “I wish to speak with you, love”

• Dropping it: “I love you”

• End of tips to the lips: “Do you love me?”

• Striking it on the hand: “I am much displeased”

• Tapping the chin gently: “I am in love with another”

• Twirling it around: “Be careful! We are watched”

• Folding it up: “Get rid of your company”

• Carrying it elevated in left hand: “Desiring acquaintance”

• Carrying it elevated in right hand: “You are too willing”

• Carrying in front of you: “No more at present”

• Letting it rest on the left cheek: “No”

• Carrying it over the right shoulder: “You can speak to me”

• Carrying it over the left shoulder: “You are too cruel”

• Letting it rest on the right cheek: “Yes”

• With handle to the lips: “Kiss me”

• Swinging it to and fro by the handle on left side: “I am engaged”

• Putting it away: “No more at present”

• Using it as a fan: “Introduce me to your company”

• Swinging it to and fro by the handle on the right side: “I am married”

This, of course, raises the question over how much of a secret code this actually was… if everyone had easy access to a code book?

Social changes in the twentieth century made parasols an anachronism. By the 1920s cloche hats and rolled stockings protected the wearer while tanned skin came to be seen as a sign of health and beauty. It also suggested that the owner didn’t have to work and was wealthy enough to sit on the beach all day. Perhaps, most of all, other ways of more direct social interaction between women and men became acceptable.

Torquay’s promenade is still there, though the post-millennial Strand is now better known for pavement pizzas, young men skirmishing, the lager and the lout. The coquette is now queen and the Smirnoff-soused bachelor impervious to anything resembling subtlety.

Consequently, the days of delicate promenading in Torquay on a Saturday night have now sadly come to an end. We will not see their like again.