On January 14th, 1858, the French Emperor Napoleon III was attacked in his capital by a gang of assassins who hurled three small bombs at his carriage. The Emperor escaped unharmed but eight imperial attendants and bystanders died and 150 others were injured.

It emerged that the terrorists were Italian nationalists, struggling to liberate their homeland from Austrian domination. Their ringleader, Felice Orsini, was quickly captured executed by guillotine.

However, this had dramatic consequences in Britain, where it sparked a political crisis that culminated in the downfall of Lord Palmerston’s government.

The conspirators had lived in Britain as refugees while they were organising their plot – even the bombs had been manufactured in Birmingham. Britain appeared willing to offer sanctuary to the enemies of France – there had been war panics from 1848 to 1859 but the Orsini Conspiracy caused further deterioration in relations and British military planning against a French invasion was stepped up.

In May 1859 Britain’s War Minister issued a circular inviting the formation of Volunteer Corps. Due to the predicted assault being from the sea, coastal towns preferred that Artillery Volunteers be enrolled.

There was already a company of Rifle Volunteers in Torquay showing local interest for joining Rifle, Artillery and Engineer Volunteer Corps. And by August 1860 there were enough Artillery Volunteer Corps (AVCs) to form an Administrative Brigade with its Headquarters at Teignmouth. It would then move to Torquay in 1863 and to Exeter in 1865.

This local enthusiasm predated the national initiative, however. It began on January 13, 1852, when a meeting was held in Exeter’s Minerva Rooms. At that meeting 70 gentlemen enrolled in the Exeter and South Devon Rifle Association. At a later meeting a letter was presented from Her Majesty Queen Victoria saying she was pleased to accept the services of the Association as the South Devon Rifle Corps- a battalion was then authorised to be raised.

It was then decided that Torquay needed its own company of Volunteers. On the 5th of February, 1853, a public meeting was held and this was agreed, and on the 28th of March the adjutant enrolled the first members. A Town Committee was then formed to promote and provide funds for the Rifle Volunteer Corps.

A number of the town’s elite joined taking the role of officers. Notably, the Volunteers were required to provide their own uniforms and arms so membership was certainly exclusive. We may also want to consider whether the imagined enemy was, not only our old enemies across the Channel but domestic troublemakers such as Torquay’s working class who had rioted in 1847 and would again in 1867.

On 29th of August 1853 the men, 80 in number, marched to Daddyhole to be drilled and to take part in a pretend skirmish with the Coastguard. It rained, however, and so the planned make-believe assault from the Coastguard’s galleys had to be called off.

Our local Volunteers seemed to be quite fond of these mock fights which became a great local attraction. On 25 July, 1855, the Torquay men, now in three divisions, assembled on what is now Belgrave Road to display their training, professionalism and dedication to the fray.

Their goal was to assault and take the nearby reservoir- this was on the site where the Hotel Nepaul would later be built on Croft Road. The reservoir had a circular form with sloping sides and fortunately resembled a fort or redoubt. Intriguingly, above the reservoir flew a red flag, the symbol of socialism and associated with left-wing politics since the French Revolution and adopted during the Revolutions of 1848.

The symbolism of this would have been known by all involved.

The reservoir’s defenders had been recruited from the workmen of Stark’s Foundry and weren’t going to surrender without putting up some stiff resistance – there may even have been some class conflict going on here.

Accordingly, the Volunteers’ advance guard was ambushed by men in rifle pits and by a hidden battery of nine guns. Eventually Torquay’s finest prevailed – as we always knew they would – the red flag was lowered and the Union Jack hoisted in its place, “amid the hearty cheers of thousands of spectators”.

The only casualty of the day was one of the men in the earthworks who was directed to discharge some rockets for dramatic effect. In doing so, a rocket fell into the bucket containing the ammunition causing an explosion, “one of the garrison was carried off to the Infirmary slightly burned”.

Fortunately we have a print to illustrate the occasion.

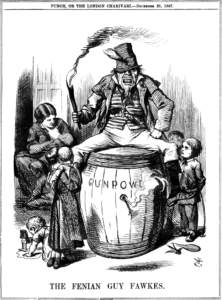

Anxiety over threats to order continued, some reasonable and others less so. In 1867 there was a rebellion in Ireland, the Fenian Rising, against British rule. Organised by the Irish Republican Brotherhood, it failed but caused panic in England.

Even though the danger was so many miles away, in December 1867 “in consequence of Fenian agitators” a force of 300 special constables was raised in Torquay.