During the nineteenth century the Industrial Revolution brought about massive economic changes to Britain. It also transformed the small villages that made up the north side of Torbay into the richest town in the country. Along with the affluent tourists, opportunities for employment brought many working people into Torquay and gradually changed how we saw ourselves.

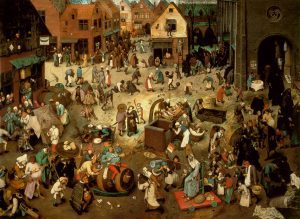

Many of those incomers brought their country ideas about enjoyment with them. These were often small-scale communal ways of life that were ritualised and dictated by the seasons. Preindustrial times had a culture where festivals, markets and fairs featured, “raucous ear-shattering noise, unpitying laughter, and the mimicking of obscenities”. They weren’t going to immediately end in an urban Torquay.

One of those main festivals was Easter which was always full of customs, folklore and traditional food. Yet, Easter in Britain had its beginnings long before the arrival of Christianity. Not only did it mark the end of the winter, it was also the finale of Lent, traditionally a time of fasting in the Christian calendar. It was therefore often a time of riotous celebration.

One of those main festivals was Easter which was always full of customs, folklore and traditional food. Yet, Easter in Britain had its beginnings long before the arrival of Christianity. Not only did it mark the end of the winter, it was also the finale of Lent, traditionally a time of fasting in the Christian calendar. It was therefore often a time of riotous celebration.

Torquay’s new residents quickly adopted and enlarged an Easter festival which had probably been around during the time of Torre Abbey’s medieval Abbots. For example, in 1867 it was reported that, “On Easter Monday Lower Union Street was obstructed by stalls and swinging boats were in great request. On Tuesday Torre Square and East Street were blocked up with swing-boats, caravans, shows and sweet stalls.”

Torquay’s new residents quickly adopted and enlarged an Easter festival which had probably been around during the time of Torre Abbey’s medieval Abbots. For example, in 1867 it was reported that, “On Easter Monday Lower Union Street was obstructed by stalls and swinging boats were in great request. On Tuesday Torre Square and East Street were blocked up with swing-boats, caravans, shows and sweet stalls.”

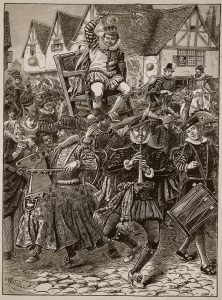

One of the peculiar features of this Torquay event was the election of a Lord of Misrule. In the countryside this was generally a peasant appointed to be in charge of the revelries, which often included drunkenness and wild partying. One suggestion is that this was a pagan survival. In the ancient Roman feast of Saturnalia, the ordinary rules of life were subverted as masters served their slaves. Some also believe that there was a darker side as the Lord of Misrule would then become a human sacrifice. References to this idea were made in the 1973 film The Wicker Man – but do avoid the terrible 2006 Nicolas Cage remake!

One of the peculiar features of this Torquay event was the election of a Lord of Misrule. In the countryside this was generally a peasant appointed to be in charge of the revelries, which often included drunkenness and wild partying. One suggestion is that this was a pagan survival. In the ancient Roman feast of Saturnalia, the ordinary rules of life were subverted as masters served their slaves. Some also believe that there was a darker side as the Lord of Misrule would then become a human sacrifice. References to this idea were made in the 1973 film The Wicker Man – but do avoid the terrible 2006 Nicolas Cage remake!

From 1867 we hear that, “At Torre the young fellows elected one of their order as Lord Mayor, and chaired him through the town, levying contributions at every public house, after which they visited Torre Abbey, where they never failed to receive a hospitable reception. The day’s perambulation invariably concluded by depositing the civic dignitary in the horse-pond at the bottom of the Avenues.” Note the symbolic ending of the Lord’s rule.

From 1867 we hear that, “At Torre the young fellows elected one of their order as Lord Mayor, and chaired him through the town, levying contributions at every public house, after which they visited Torre Abbey, where they never failed to receive a hospitable reception. The day’s perambulation invariably concluded by depositing the civic dignitary in the horse-pond at the bottom of the Avenues.” Note the symbolic ending of the Lord’s rule.

Before the Industrial Revolution there was, for many, more free time, with long weekends created by Monday holidays for saint’s days. With the move to Torquay, Sundays became the only common free day – in the case of many working people in service not even this day remained free as they had to undertake domestic chores. The new labour process of regular and intense working hours produced a new type of leisure – much silent work serving in one of the 500 villas that covered Torquay’s seven hills, alternating with noisy drunken riot. This public rowdiness associated with working-class leisure activities, poor time keeping, and drunkenness all conflicted with the demands of industrial and service labour. As our growing elite became increasingly powerful, their attitudes and values changed the leisure opportunities of Torquay’s working folk. Gradually the traditional fairs were closed down or more closely controlled.

In Torquay we read that, “At length the disorders to which the fair gave rise compelled the Local Board of Health to take decisive measures. And they accordingly directed the police to prevent the thoroughfares from being disrupted. So the fairs were extinguished.”

In Torquay we read that, “At length the disorders to which the fair gave rise compelled the Local Board of Health to take decisive measures. And they accordingly directed the police to prevent the thoroughfares from being disrupted. So the fairs were extinguished.”

Nevertheless, these efforts don’t appear to have been entirely successful. From the Torquay Directory of April 1878 we have the following report, “It was hoped that as the Torre Abbey Field were covered with buildings, the disorderly scenes which occur there on a Good Friday would have been put an end to. Last Friday, however, proved to be no exception to the rule, and pedestrians who had to make their way to the railway station had to pass through groups of men playing pitch and toss, football, and sometimes to make a detour to avoid the young men and girls who were indulging in the vulgar amusement of ‘kiss in the ring’. Rowdyism was rampant, for the few policemen on duty were powerless to check it. The behaviour and language of those who partcipated in the so-called sports were abominable. In one of the avenues refreshments were dispensed by itinerant dealers, greatly to the annoyance of the residents, and it was not till late in the evening when rain fell heavily that the disorderly crew dispersed.”

Nevertheless, these efforts don’t appear to have been entirely successful. From the Torquay Directory of April 1878 we have the following report, “It was hoped that as the Torre Abbey Field were covered with buildings, the disorderly scenes which occur there on a Good Friday would have been put an end to. Last Friday, however, proved to be no exception to the rule, and pedestrians who had to make their way to the railway station had to pass through groups of men playing pitch and toss, football, and sometimes to make a detour to avoid the young men and girls who were indulging in the vulgar amusement of ‘kiss in the ring’. Rowdyism was rampant, for the few policemen on duty were powerless to check it. The behaviour and language of those who partcipated in the so-called sports were abominable. In one of the avenues refreshments were dispensed by itinerant dealers, greatly to the annoyance of the residents, and it was not till late in the evening when rain fell heavily that the disorderly crew dispersed.”

It took decades to suppress the worst excesses of our ancestors and the campaign to eliminate working class misbehaviour never fully succeeded. Now the festival tradition is back – 14 million UK adults planned on attending a festival in 2016. For example, here’s our closest large event, the Levellers’ Beautiful Days, held every year near Honiton:

It took decades to suppress the worst excesses of our ancestors and the campaign to eliminate working class misbehaviour never fully succeeded. Now the festival tradition is back – 14 million UK adults planned on attending a festival in 2016. For example, here’s our closest large event, the Levellers’ Beautiful Days, held every year near Honiton: