Torre Abbey’s tithe barn was built around 1200 to store taxes paid to the abbey in the form of grain, hay and other farm produce. For centuries, however, it’s been known to locals as the Spanish Barn.

Its place in history was secured in 1588 when the Nuestra Senora del Rosario became among the first of the Spanish Armada invasion force to fall victim to the English fleet. That’s the ship in the picture. The captured ship was towed to nearby Torbay where the crew were landed, probably on Abbey Sands, to be received by a guard of demi-lances – a type of heavy cavalryman quartered at St Marychurch.

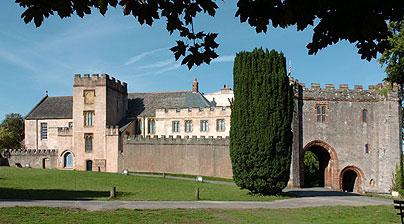

Drake sent the commander of the Rosario, Don Pedro de Valdés, to the Queen while the other 397 prisoners were held in the Barn, making it the only surviving Armada prison in England.

Initially a general order had been given that all Spaniards should be executed wherever found. This order was later cancelled, though the Sheriff of Devon remained convinced that any prisoners should have, in his words, “been made water spaniels”.

Local people were understandably hostile to the new arrivals. The inhabitants of Brixham, Paignton, Cockington, Torre and St Marychurch flocked to see the captives and there were angry demonstrations. A letter to the Privy Council on July 27 reads: “The charge of keeping them is great, the perell greater, and the discontent over country greatest of all that a nation be so mitche misliking unto them should remayne amongst them.”

Giving some idea of the depth of feeling against the invaders and the general fear of local Catholic sympathisers, there is a story of a farmer surreptitiously giving food to the prisoners. Being discovered he was hanged from a nearby tree.

It was accordingly resolved to relocate the prisoners quickly and after a stay of around a fortnight they were sorted into “those of name and quality” and “the rest of baser sort,” and sent out of the Bay. On August 29 Cary and Gilbert wrote to inform the Privy Council: “The prisoners, being in number 397, whereof we sent to my Lord Lieutenant five of the chiefest of them, whom his Lordship hath committed to the town prison of Exeter, and we have put 226 in our Bridewell… the rest, which are 166, for the ease of our country from the watching and guarding of them and conveying of their provisions and victuals unto them, which was very burdensome to our people in this time of harvest, we have therefore placed them aboard the Spanish shippe.”

It was in the years that followed that the myths and legends of the Spaniards stay at the Barn started to appear. It was already known as the Spanish Court In 1662 when John Stowell conveyed Torre Abbey to Sir George Cary and the discovery of cannon balls lodged in the garden walls and that of “human skulls and bones that have been frequently dug up” may have contributed towards myths of starvation and massacre.

By the 18th century the event was becoming confused in local memory. For example, Reverend JB Swete, who visited Torquay in 1778, wrote that “a chaff cutter therein employed told me that it was once nearly filled with the dead bodies of Spaniards, who having landed with an intent of plundering the abbey, were kept on shore by means of an English fleet that unexpectedly entered the Bay, and flying for refuge to this barn, were there shut up and starved to death.”

Another story tells that in Coles Lane, described as “a narrow steep road between Upton and St Marychurch… the blood of the Spaniards ran like water”. This was allegedly due to a failed escape attempt when the prisoners were being conveyed from Torre Abbey to Exeter, though this appears to be an exaggeration of what may have occurred.

JT White in his 1878 History of Torquay referred with thinly disguised scorn on those “village gossips” who “affirm that the spirits of the slaughtered Spaniards visit the spot at those hours when it is supposed such visitants walk the earth”.

Certainly the Spanish Barn was overcrowded, each prisoner only having around eight square feet to themselves. Some did die from wounds, privation or exposure during their stay. Yet, only around 15 Spaniards lost their lives between arriving at the Spanish Barn and when they were counted again.

They were not murdered or deliberately starved as they were a valuable commodity. Indeed, negotiations to ransom the prisoners began shortly after their arrival in England. By the close of 1589 the majority of them were officially freed – Don Pedro de Valdés was freed in February 1593 upon payment of a ransom of £3550. Generally, Spaniards taken in the Channel seem to have been treated well and quickly repatriated. On the other hand, those captured in Ireland were usually put to death. It’s estimated that 5,000 members of the Armada perished in Ireland.

The best known of the Torre Abbey legends is, of course, that of the Spanish Lady. The first recording of the story appears to be by JT White who, indicating his Victorian middle class disdain for vulgar rural folk tales, again ascribed it to “village gossips”. He goes on to briefly mention the “Spanish lady, whose devoted attachment to an officer of the expedition induced her to don male attire in order to join the armada, shrouded in a gracefully flowing mantilla, may also at times be seen gliding along the lane. The spectre, however, very discreetly retires on the approach of a wayfarer.”

By the early 20th century the brief few lines of the Spanish Lady legend had been transformed into Gothic melodrama, as in the book Tales of Torquay. Now we had “serenading and stolen meetings in the glamourous atmosphere of Andalusia” before our tragic couple found themselves suffering alongside their compatriots in “cramped and unhealthy quarters… It was little wonder that sickness broke out amongst them. The poor little flower of southern Spain quickly faded in this dreadful place, and a last parting took place between the lovers.”

Though it seems very unlikely in staunchly Protestant Torbay, there was fortunately a Catholic priest who “resided in the ruined Abbey” who was “permitted to administer the last rites, but her troubled spirit found no rest… it is still to be seen drifting slowly and rather wearily through the Abbey park towards the Spanish Barn”.

We’re not alone, however, in having a resident wandering female ghost. The Spanish Lady is our version of the White Lady archetype. Such supernatural White Ladies can be found throughout the world, and in many cultures, and are usually associated with the tragic loss of a loved one.