The most familiar of Torquay’s supernatural tales is of the Spanish Lady of Torre Abbey. The setting is the Abbey’s barn, built around 1200 and generally accepted to be a tithe barn designed to store taxes in the form of grain, hay and other farm produce.

For centuries it has been known as the ‘Spanish Barn’, its place in history being secured when the ‘Nuestra Senora del Rosario’ became among the first of the Spanish Armada to fall victim to the English fleet in 1588.

The captured ship was towed to the nearby Bay where the crew were landed, probably on Abbey Sands to be received by a guard of demi-lances, a type of heavy cavalryman quartered at St Marychurch. The commander of the Rosario, Don Pedro de Valdés, was quickly sent to the Queen while the other 397 prisoners were held in the Barn, making it the only surviving Armada prison in England.

While in the early days of Armada panic a general order had been given that all captured Spaniards should be executed, this was later rescinded. Nonetheless, the Sheriff of Devon remained convinced that any prisoners should have “been made water spaniels”. Certainly, the Spaniards were unwelcome and expensive guests and the angry inhabitants of Brixham, Paignton, Cockington, Torre and St Marychurch journeyed to the Abbey to make their feelings known.

This situation was recognised in a letter to the Privy Council on July 27: “The charge of keeping them is great, the perell greater, and the discontent over country greatest of all that a nation be so mitche misliking unto them should remayne amongst them.”

It was in later years that the stories began. The Barn was already known as the ‘Spanish Court’ by 1662 and the discovery of cannon balls lodged in the garden walls and that of “human skulls and bones that have been frequently dug up” may have contributed towards myths of starvation and massacre.

As memory of the event faded, embroidered tales began to appear and it was reported that, “Hundreds of captured Spanish Armada sailors were imprisoned in Torre Abbey’s Spanish Barn and many of them died there…”

Another story tells that in Upton, “The blood of the Spaniards ran like water… the spirits of the slaughtered Spaniards visit the spot”.

These reports are not accurate. Only around fifteen Spaniards lost their lives, possibly from injuries acquired in the fighting, between arriving at the Spanish Barn and when they were counted again. While the Barn was certainly overcrowded, the prisoners were too valuable not to be ransomed and, following common practice, negotiations commenced shortly after their arrival in England. By the end of 1589 the majority of them were officially freed; Don Pedro de Valdés was released in February 1593 upon payment of a ransom of £3,550.

Torquay’s myth-making then created the Spanish Lady story of a young woman, alternatively a wife or fiancée, disguised as a boy sailor on board the Spanish ship. Her motivation for doing this was that she could be among the first to enjoy the spoils of a successful invasion. She, however, becomes ill and dies in the overcrowded Barn.

Yet there appears to be no record of the tale until the late nineteenth century when we read of the love that led her “to don male attire in order to join the armada.” By the early twentieth century these few lines had become melodrama: “The poor little flower of southern Spain quickly faded in this dreadful place. Her troubled spirit is still to be seen drifting slowly and rather wearily through the Abbey park”.

So where did the story come from?

‘White Lady’ ghosts are very common across the world – Berry Pomeroy Castle has one.

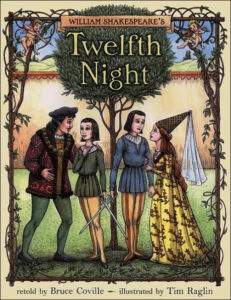

But we may need to look at Shakespeare for the cross-dressing trope. The bard never shied away from confusing gender-swaps. In ‘As You Like It’ Rosalind disguises herself as a young man named Ganymede after she is banished from the royal court; in ‘The Merchant of Venice’ the wealthy heiress Portia dresses as a doctor in order to defend Antonio; in Cymbeline a woman takes on the appearance of a boy to survive a murder ordered by her lover. The closest precedent, however, would be the romantic comedy ‘Twelfth Night’ in which a shipwreck separates Viola from her twin brother, and so she disguises herself as a man.

All social classes in nineteenth century Torquay would have been aware of these plot-lines…