If you drive down through Torquay town centre in the direction of the Harbour you have to take a detour to avoid the pedestrianised Lower Union Street, taking you behind Primark and WH Smiths. This narrow street is called Pimlico and for over a century was Torquay’s slum area – a place of poverty, crime, prostitution, violence and disease. The lives of the people who lived and died there were seldom recorded – except in exceptional circumstances. Though we do have a glimpse into the lives of those residents through inquests into unexplained deaths which were covered in the local newspaper the Torquay Times and South Devon Advertiser.

On 24 July 1875 an inquest was held into the violent death of Elizabeth Croker who was, “a very hard-working and industrious woman”. Elizabeth and a man called Buckpitt lived together in a lodging house. Buckpitt was a lumper – a kind of docker who unloaded trawlers – and the two “lived pretty comfortably together, except at times when he was drunk”. Just before Maria died Buckpitt had been seen to kick and strike her across the face with his dinner of bread and meat in a cloth. Elizabeth cried out, “Why did you do that for after my hard day’s work?”It wasn’t the first time – on another occasion Buckpitt had struck Elizabeth in the face with his hand, knocking her to the floor.

After this last assault Elizabeth complained of a pain in her left side and died two days later. However, not being able to definitely link the attack with Elizabeth losing her life, the Jury returned a verdict of ‘Death from Natural Causes.’ Nevertheless, Buckpitt was chastised by the Coroner, who warned him about his conduct. The Coroner believed Buckpitt was able to act, “in a proper manner when sober, but his conduct when tipsy was very bad. If Buckpitt should ever be allied to another woman he hoped he would treat her kindly.”

Alcohol also played its part in the short twelve month life of Marie James who died in 1898. Marie was the daughter of Pimlico’s Henry James, a horse-drawn vehicle driver, and “an industrious, sober, hard working fellow, in the employ of Messrs. Shapley and Sons, grocers of Torquay”. Henry started work at 7am and never left before 9pm, sometimes seven days a week and so was rarely at home.

These were the days before social workers would protect children from abuse though there was a charity which had been set up in 1883 – the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC). The James’ household was visited by their Inspector Brown. On one visit he found only a single crust of dry bread for the four children – year-old Marie, and others aged seven, five and three years. In all, four adults and five children occupied four rooms. Both parents were absent, the children’s mother Mrs James being in the habit of going to a neighbour’s drinking. Marie was found to be dirty, nearly always lying in the cradle, and when touched seemed too weak to cry. On one occasion vermin were on her face. When Detective Gregory later visited the house, three of the children were huddled together under a table, while the little girl was upstairs lying on a wet bed, “with little clothes on”. Her head was a mass of sores, and her neck and arms covered with a rash. Marie was described as being, “in an emaciated condition” and weighed 10lbs with a frock and skirt on – she should have weighed about 19lb. The doctor described her as “a ghastly object” and noted that, “the baneful effects of alcohol had been transmitted to the child”. To protect her she was immediately removed to Newton Abbot Workhouse where, even though, “every care was bestowed on the child at the workhouse, it (sic) gradually pined away and died”. The Jury found that Marie had died from ‘Natural Causes’, hastened by her alcoholic mother’s culpable neglect. Mrs James was sent to prison in Exeter.

Indeed, there was little support for the vulnerable. In April 1901 Edward Manley, a 47 year old porter living in Happaway Row, Stentiford’s Hill, was summonsed to explain how his mother Maria Dunn, aged 73, had died. They had lived together in a two-roomed tenement and occupied the same bedroom. Edward was asked, “Why did you allow her to lie there and die like a dog without seeing anyone? How it is the place was in such a state of filth and not fit for a human being to live in?”

Maria had died sitting in an easy chair, having been there for a fortnight. When Dr Dixon Cook was called to the house he said he had never seen a place so filthy. The son was there, but he was so begrimed with dirt that witnesses, “thought he was a foreigner”. There was only a bed and couch and Maria was found sitting in that chair covered with an old shawl – the remainder of the body was naked. However, “The son appeared to be a very weak-minded sort of a chap who would do just what his mother told him without considering his responsibility in the least”. A verdict of ‘Natural Causes’ was reached.

In November 1889 the Coroner’s Jury investigated the death of a girl in Pimlico. When Dr Gardner visited he found Annie Hall, a very sick nineteen year old laundry worker, and he quickly suspected poisoning. Annie was hysterical and said something about her “young man” having threatened to “Jack-the-Ripper” her. She died the next day. Dr Gardner asked the girl’s mother Mrs Hall – “a middle aged, short, and stoutish woman” – if Annie had taken poison. This was denied. The Police investigated but, although Mrs Hall’s evidence was, “vague, reluctant and contradictory” they eventually discovered that Mrs Hall had been drinking in the Devon Arms when she had been told that Annie was ill. Detective Bond stated that Mrs Hall had at first denied that her daughter had poisoned herself, but had eventually admitted to finding and destroying both a bottle and a glass which had contained phosphorus rat poison.

When questioned, Annie’s father William – a fisherman and “a short, thick-set man leaned against the steps of the witness box, as though it were an effort to stand and throw light upon the sad death of his daughter.” His evidence was, “hesitatory and occasionally contradictory” and he appeared “to have little concern in the investigation”. He stated that he woke to see his daughter, evidently poisoned, but he “didn’t take much notice of the affair.” He took no steps to obtain medical assistance, saw the poison bottle and handed it to his wife who destroyed it.

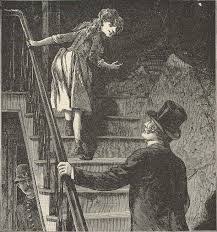

Annie’s “sweetheart” was Henry Pym – “a short young fellow of about 26” – who was confronted with evidence that the two had a violent relationship with “rows” frequently taking place. He had been seen hitting Annie outside the Devon Arms and earlier that week she had fallen down stairs, though Henry, “had not taken the trouble to pick the poor girl up”. On the witness stand “Henry was alternately reticent and communicative.” When Annie was discovered Henry found that she had “taken something” which glistened on her mouth. He picked her up, with the aid of her mother, and wiped the phosphorus from her lips, “because so many people were coming in”. Then he snatched a bottle from her pocket, or took it from her hands – both of which explanations he tendered to the Coroner – and then went “straight to bed, as it wasn’t anything to do with him.” His theory was that she took the phosphorus because she was “flurried – jealous about other girls, like,” and because she had previously threatened to do so.

In court it was revealed that Annie displayed no signs of pregnancy, but that she was insured in the Prudential Society. It was agreed that Annie had poisoned herself whilst ‘Temporarily Insane’, but that her parents and partner had, “been guilty of the grossest indifference and neglect of the condition of the deceased”.

These are just a few of the many cases covered by the Torquay Times, but they do give a glimpse into the lives of Torquinians before the welfare state, the NHS, and a police force which these days takes neglect and violence against women much more seriously.

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us