In April of 1937 Torquay had two guests, unwelcome to many local people who were well aware of the true nature of their visitors. These callers were the German battleship SMS Schlesien and the German Ambassador Joachim von Ribbentrop.

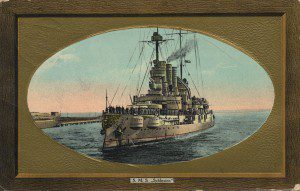

SMS Schlesien came to the Bay as part of a charm offensive by Nazi Germany. Launched on 28 May 1906, she was one of five battleships built for the Kaiserlichte Marine and commissioned into the Navy on 5 May 1908. However, she was already out-dated by the time she entered service, being inferior in size, armour, firepower and speed to the revolutionary new battleship HMS Dreadnought.

The Schlesien had served with the German fleet during the first two years of the First World War and was present at the battle of Jutland in 1916. In 1917 she became a training ship. The Treaty of Versailles allowed the German navy to retain eight obsolete battleships, which included the Schlesien, to defend the German coast.

In 1937 she was in the Bay to meet local dignitaries and the German ambassador, von Ribbentrop. A crowd of 300 met the Nazi party at Torquay Station and then the visiting dignitaries were driven to a reception at the Marine Spa – now Living Coasts. Ribbentrop, Frau Ribbentrop, Naval Attaché Admiral E Wassner, commander of the Schlesien Captain von Seebach, the German Vice Consul at Plymouth Mr Carlile Davies, and a number of ships officers were introduced by the Mayor Mr A Denys Phillips to members and officials of the Town Council.

At the reception Ribbentrop was on usual charming form: ‘I may, I hope, really believe that the contact which has taken place between the crew of this ship and the citizens of your town might prove to be a new tie between our two countries. I am sure you will agree with me that these two countries must understand each other.’

Toasting the visitors, the Mayor responded: ‘We know your visit will be a short one but nevertheless I hope it will be a happy one and you will take back pleasant memories of your short stay in our town of Torquay.’ The reception continued with ‘three cheers for the guests’.

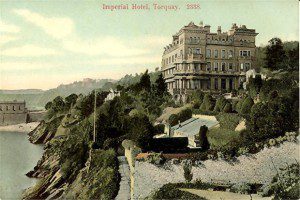

The Nazi party then embarked from Haldon Pier for the Schlesien where Ribbentrop was piped on board to review a guard of honour on the quarter deck. He was, ‘introduced to about 30 officers each of whom remained with their hand at their peaked cap while the ambassador gave the Nazi salute’. The ambassador later attended a small dinner party at the Imperial Hotel at which there were around 30 guests, including the mayoral party. The crew of the ship later went on to play Torquay United in a testimonial match. There’s a photo of the sailors giving a Nazi salute just before the game – United won.

Both Ribbentrop and the Schlesien had long careers and neither survived the war.

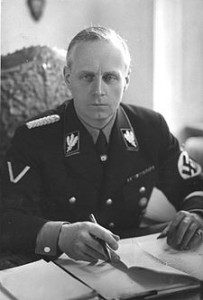

Joachim von Ribbentrop (1893-1946) was the son of a German Army officer. He spent time in France and England before moving to Canada where he worked on the reconstruction of the Quebec Bridge and the Canadian Pacific Railroad. He was then employed as a journalist in New York and Boston.

On the outbreak of the First World War Ribbentrop returned to Germany where he joined the army and won the Iron Cross. After being seriously wounded in 1917 he joined the War Ministry and was a member of the German delegation that attended the Paris Peace Conference.

After leaving the army Ribbentrop joined the National Socialist German Workers Party in May 1932. He was rapidly promoted and in 1933 became Hitler’s foreign affairs adviser. Hitler appointed Ribbentrop as the ambassador to London in August 1936, his main tasks being to persuade the British government not to get involved in Germany’s territorial ambitions and to work together against the Soviet Union. Hence, the charm offensive which involved the Torquay visit.

However, Ribbentrop’s behaviour alienated some British opinion. When he presented his credentials to George VI he gave the Hitler salute, he posted SS guards outside the German Embassy and flew swastika flags on official cars. On 4th February 1938 Ribbentrop became Germany’s foreign minister. Hitler’s private secretary Traudl Junge described him as: ‘A very odd man. The impression he made on me was of someone absent-minded and slightly dreamy, and if I hadn’t known that he was Foreign Minister I’d have said he was a cranky eccentric leading a strange life of his own.’

Ribbentrop worked closely with Hitler in his negotiations with the British and French governments and in August 1939 arranged the signing of the Nazi-Soviet pact. In 1940 Hitler was planning the invasion of the Soviet Union and sent Ribbentrop to negotiate a new treaty with Japan.

During the war Rippentrop became a background figure but was arrested and charged with war crimes in June 1945. He denied knowledge of the concentration camps and the Holocaust, but was found guilty at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trial and was executed on 16th October 1946.

The focus of Ribbentrop’s visit to Torquay also didn’t survive the conflict. The Schlesien saw limited combat, including the invasion of Norway in 1940, and ended her career as an anti-aircraft ship in the Baltic. In April 1945 she steamed to Swinemunde to restock her ammunition and evacuate wounded soldiers. During these duties she struck a mine and sank in shallow water. However, much of her superstructure, including the main battery, remained above water. For the remaining months of the war, the Schlesien used her heavy artillery to provide support for retreating German troops. After the end of the war, the Schlesien was broken up, though some parts of the ship remained until the 1970s.