Torquay was once the richest town in England. We had a large number of very wealthy and educated residents and visitors who had a lot of time on their hands and an interest in exploring ideas outside of mainstream religion and philosophy. Consequently, the town developed a reputation as being one of the centres of occult thought and practice in Victorian and Edwardian Britain.

These weren’t just news ideas of course. Old beliefs about the supernatural lingered on in urban Torquay. In May 1875 the clerk of Torquay’s magistrates, a Mr Hearder, received an application by a poor old woman in Chelston who believed that her husband had died from the effects of witchcraft.

This was unusual as the Victorians believed that a belief in witchcraft had died out. Indeed, way back in 1735, the Witchcraft Act had abolished witchcraft as a crime – the state had decided that maleficence didn’t exist. There was another reason why it was unusual for the authorities to be consulted on witchcraft. This was that the usual resort of those who feared they were being bewitched was to employ the services of a cunning-man or woman. Each community had a practitioner of magic who could locate treasure, cast spells and offer protection from supernatural threats. Cunning-folk, however, were usually to be found in rural areas and some were well-known figures: in the 1860s John Collander, the ‘white witch of Newton Abbot’, was apparently quite popular with women. Unlike witches, cunning folk weren’t seen as the enemies of Christianity, but often allies. For instance, in 1868 an Ashburton cunning-woman was called in to investigate the stealing of books from the music loft of the church. She reportedly identified the thieves by reading playing cards. However, it was still illegal to pretend to be able to call up spirits, foretell the future, cast spells, and discover the whereabouts of stolen goods. The penalty was to be punished as a vagrant and be subject to fines and imprisonment.

One of the difficulties that the authorities had was in deciding who could reasonably claim to have access to the supernatural and who was a charlatan. It looks like the Teignmouth astrologer William Priestly was the latter. In 1893 William advertised that, for payment, he could send single people a photograph of their future husband or wife. He was apparently mailing identical photographs to people across the county. His foretelling powers unfortunately failed, and he received a month’s hard labour and costs.

On the other hand, many respectable people were committed to Spiritualism, a practice that believes that the spirits of the dead have the ability to communicate with the living. Spiritualism developed and reached its peak in membership from the 1840s to the 1920s. One such prominent Spiritualist and Torquay visitor was the Sherlock Holmes author Conan Doyle. He wrote ‘The History of Spiritualism’ in 1926, and was a member of the paranormal investigation organisation The Ghost Club. Proclaiming his belief in the afterlife, on August 5, 1920, Conan Doyle gave a lecture entitled ‘Death and the Hereafter’ at Torquay Town Hall to a mainly female audience. The meeting was presided over by local builder and Freemason Henry Paul Rabbich, the then President of Paignton Spiritualist Society and Vice-President of the Southern Counties Union of Spiritualists.

It’s also worth noting how an interest in the occult was often associated with a commitment to progressive ideas. For example, the St Marychurch novelist Annie Hall Cudlip (1838–1918) controversially dealt with subjects such as the sexuality of young girls and illegitimate pregnancy. Annie was also involved in animal rights groups and wrote about animal cruelty. In February 1873 Annie joined her close friend Florence Marryat in a visit to a London séance. Florence later wrote down her experiences in a highly successful non-fiction book, ‘There Is No Death’ (1891) in which she described what they saw and the pair’s subsequent conversion to Spiritualism.

The occult could cover a wide range of beliefs associated with the esoteric and mystical. For example, in the 1880s a group calling itself the Order of the Temple occupied ‘Cloudlands’, a house in Chelston. Their leader, the Spiritualist Countess Marie Borel believed that her adopted son Prince Baptiste St John Borel, also known as ‘Mr Northlew’, had special powers. The Countess understood herself to be the “woman clothed with the sun” who was to “bear the child to rule the world with a rod of iron”. Yet, we hear nothing more of her or the Prince, so sadly the Messiah wasn’t to come from Chelston.

Certainly some Spiritualists would reject the inclusion of their faith in an article on the occult. However, the term simply refers to a search for knowledge of the hidden, and the exploration of a deeper spiritual reality that extends beyond reason and the physical sciences. It doesn’t necessarily mean any alternative, or hostility, to the Christian faith.

Accordingly, Torquay’s ‘secret societies’, when they were exploring hidden knowledge, could also be referred to as occult. Though now primarily philanthropic organisations, Torquay’s Freemasons (founded in 1810), the Oddfellows (1856), and the Foresters (1858) all claimed to have their roots in antiquity – in ancient Egypt, Rome or Anglo-Saxon Britain. They also used rituals that have, in the past, concerned the established Church.

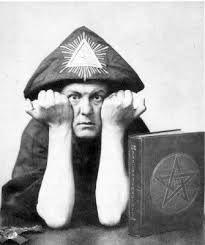

On the other hand, one Torquay resident revelled in his reputation as an occult practitioner of ‘Magick’. This was Aleister Crowley, (“the wickedest man in the world” and pictured above) who lived in Barton. Crowley (1875-1947) was responsible for founding the religious philosophy of Thelema and is now seen as one of the most influential occultists of all time.

Most towns have a variety of legends about ghosts and the supernatural. Yet, how many of the dozens of supernatural tales of Torquay were made up by Inventive Victorian authors and tourist guides is open to debate. Nevertheless, it’s worth noting that odd stories have long been associated with possible pre-Christian sites such as those at St Michael’s Chapel, Daison and Gallows Gate.

Better documented are the claims of notable residents and visitors. For example, in 1920, the writer Beverley Nichols, his brother and a friend, Lord Saint Audries, visited Torquay’s version of Amityville, ‘Castel a Mare’ in Middle Warberry Rd. The three intrepid ghost hunters were reportedly assaulted by an invisible force.

Another instance is that of Rudyard Kipling who lived in Rock House in Maidencombe between 1896 and 1898. Soon after taking up residence, Kipling began to complain about “a gathering blackness of mind and sorrow of the heart”. Thirty years later, he and his wife paid another visit. Rock House was “quite unchanged, the same brooding spirit of deep, deep Despondency within the open, lit rooms”.

We’ve also had a variety of occult and horror authors living in town. Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873), lived in Argyll Hall on Warren Road. A hugely successful poet, playwright, and novelist, Edward (pictured above) had an in-depth knowledge of the occult and he included esoteric ideas in his work. This earned him the respect of the leading figures of the nineteenth century occult revival. Consequently, a number of societies claiming hidden knowledge have seen him as one of their own. He has been suggested as a member of organisations that have sometimes been active in the Bay, including the Rosicrucians, Theosophists and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Debate continues over how close he actually was to these groups.

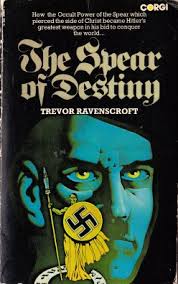

In 1973 the historian Trevor Ravenscroft published ‘The Spear of Destiny’, a book which “remains one of the most important texts in the field of Nazi occultism”. There was also a follow-up, ‘The Mark of the Beast’. Some see Trevor’s books as classics of occult history while others consider them no more than inventive fiction.

Continuing the long tradition of Torquay’s association with horror and supernatural fiction is Brian Lumley, the author of the Necroscope vampire novels who lived in Shedden Hill.

Belief in the occult and supernatural has changed over the years. Nevertheless, there are many groups and individuals in the Bay who maintain an interest in the hidden, the unseen, and the possible. They include: members of our Spiritualist, Pagan, and Theosophist communities; the buyers of magic crystals on sale in Fleet Street; participants in ghost walks and celebrations such as Halloween; and readers of astrology columns in local newspapers.