In 1803 the small villages that made up Torbay prepared to be invaded.

Evacuation plans were drawn up and the militia assembled to meet the massive French flotilla that was expected to appear on the horizon.

France had long had envious eyes on Britain and had drawn up invasion plans by the Ancien Regime in 1744, 1759, and 1779.

France had long had envious eyes on Britain and had drawn up invasion plans by the Ancien Regime in 1744, 1759, and 1779.

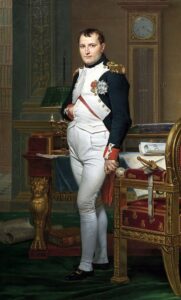

However, this time it was more serious under the determined Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. French attempts to invade Ireland in order to destabilise the United Kingdom, and as a stepping-stone to Britain, had already occurred in 1796. In 1798 the first French ‘Army of England’ had gathered on the Channel coast. However, this invasion was sidelined by Napoleon’s concentration on campaigns in Egypt and Austria, and shelved in 1802 by the Peace of Amiens.

New preparations for an invasion of the United Kingdom began soon after another outbreak of war in 1803.

New preparations for an invasion of the United Kingdom began soon after another outbreak of war in 1803.

An army of 200,000 men, known as the Armée des côtes de l’Océan (Army of the Ocean Coasts) or the Armée d’Angleterre (Army of England), was gathered and trained at camps at Boulogne (pictured), Bruges and Montreuil.

The British Regular army stood at 132,000 men, with 18,000 in Ireland and only 50,000 at home – the rest serving abroad- so the situation was perilous.

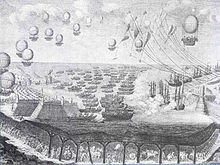

A French ‘National Flotilla’ of invasion barges was built in Channel ports along the coasts of France and the Netherlands, port facilities at Boulogne were improved and forts built. For his planned subsidiary invasion of Ireland, Napoleon had formed an Irish Legion to create an indigenous part of his 20,000-man Corps d’Irelande.

With such an international force, Napoleon was expecting to overwhelm the British- to celebrate the invasion’s anticipated success a medal was struck and a triumphal column erected at Boulogne.

These massively expensive preparations were financed by the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, whereby France ceded her huge North American territories to the United States in return for a payment of 50 million French francs. Ironically, the United States had partly funded the purchase by means of a loan from Baring Brothers, a British bank. That’s the same bank which collapsed in 1995 after suffering losses of £827 million.

These massively expensive preparations were financed by the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, whereby France ceded her huge North American territories to the United States in return for a payment of 50 million French francs. Ironically, the United States had partly funded the purchase by means of a loan from Baring Brothers, a British bank. That’s the same bank which collapsed in 1995 after suffering losses of £827 million.

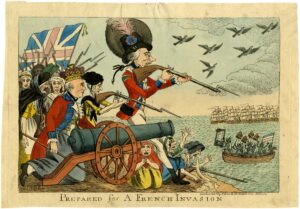

The flotilla and encampment at Boulogne were clearly visible from the south coast of England, so we knew what was being planned. In response we had plenty of opportunity to prepare for the coming assault. Martello towers were built along the coast, militias were raised, Dover Castle had underground tunnels added to garrison more troops, and the Royal Military Canal was cut to impede Napoleon’s progress into England.

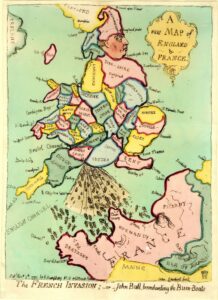

Wild rumours of a massive flat French invasion raft powered by windmills and paddle-wheels and a secretly-dug channel tunnel spread through the Press, as did caricatures ridiculing the prospect of invasion. On the other hand, Napoleon did seriously consider using a fleet of troop-carrying balloons- the prospect capturing the imagination of the British print media.

Wild rumours of a massive flat French invasion raft powered by windmills and paddle-wheels and a secretly-dug channel tunnel spread through the Press, as did caricatures ridiculing the prospect of invasion. On the other hand, Napoleon did seriously consider using a fleet of troop-carrying balloons- the prospect capturing the imagination of the British print media.

So the south east was heavily defended and well prepared.

So the south east was heavily defended and well prepared.

This suggested that Napoleon would land his invasion army further along the coast, and the prime contender was the relatively undefended Torbay. Indeed, we had seen an ‘invasion’ before – in 1688 which started the Glorious Revolution.

Torbay began to prepare for the expected onslaught. We were vastly outnumbered by those 200,000 seasoned French troops that had already defeated the best armies in Europe. But we were prepared to fight. This was the original Dad’s Army. And whether Boney’s Imperial Old Guard would have stood much of a chance pitted against the seasoned cider-drinkers of Torre, Cockington, Upton and Fleete is debateable.

In Torquay, orders were given by the town’s magistrates to make every preparation. Local Volunteers, then called the Fencibles, were held in readiness and plans were put in place for a large scale evacuation. It was planned to remove the inhabitants of Torbay, along with their goods, to Dartmoor.

In Torquay, orders were given by the town’s magistrates to make every preparation. Local Volunteers, then called the Fencibles, were held in readiness and plans were put in place for a large scale evacuation. It was planned to remove the inhabitants of Torbay, along with their goods, to Dartmoor.

In November of 1803 a notice was issued:

“Tormoham, 9th November 1803. At a very respectable and numerous meeting of the inhabitants, held at the Crown and Anchor (in Swan Street) on Tuesday, the 8th inst., it was unanimously resolved- 1st. That the infirm, and children under the age of eight years, who are incapable of walking ten miles in one day, shall, in the case of an alarm of the enemy, be assembled in three divisions: 1st, Torquay; 2nd, Tor; and 3rd, Upton, at the following places of rendezvous- (1) Baldson at the head of Abbey Road, (2) Small Hill, and (3) top of Stantaway Hill.”

Each owner was then instructed to send a horse or cart to these meeting points. The meeting concluded, “It was also recommended by the said meeting that those persons who are not employed in any particular service should, immediately on an alarm, meet the Rev. W. Kitson at the church (St Saviours off Lucius Street), to consult in what manner they can render the greatest assistance to their neighbours and country”. This was signed by “William Kitson, superintendent”.

Before the flotilla could cross, however – as Hitler realised in a later invasion plan – Napoleon had to gain naval control of the Channel.

Before the flotilla could cross, however – as Hitler realised in a later invasion plan – Napoleon had to gain naval control of the Channel.

He wrote, “Let us be masters of the Channel for six hours and we are masters of the world.”

He envisaged doing this by having the Brest and Toulon Franco-Spanish fleets break out from Nelson’s British blockade, and then sail across the Atlantic to threaten the West Indies, This, it was intended, would draw off the Royal Navy. The French could then quickly sail back across the Atlantic to Europe, land a force in Ireland, take control of the Channel and defend and transport the invasion force. All before the pursuing British could return to stop them.

He envisaged doing this by having the Brest and Toulon Franco-Spanish fleets break out from Nelson’s British blockade, and then sail across the Atlantic to threaten the West Indies, This, it was intended, would draw off the Royal Navy. The French could then quickly sail back across the Atlantic to Europe, land a force in Ireland, take control of the Channel and defend and transport the invasion force. All before the pursuing British could return to stop them.

This bold ploy was typical of Napoleon and relied on fast manoeuvres and surprise. Yet it was more suited to marching armies than to sea warfare and the plan failed.

In August 1805 Napoleon finally accepted that his amphibious assault on Britain wasn’t going to happen, and so he used his invasion army as the core of the new Grand Armee and had it march eastwards to begin the Ulm Campaign.

In August 1805 Napoleon finally accepted that his amphibious assault on Britain wasn’t going to happen, and so he used his invasion army as the core of the new Grand Armee and had it march eastwards to begin the Ulm Campaign.

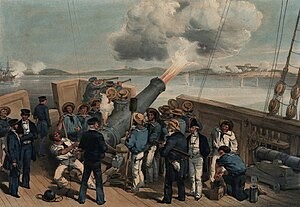

Of course, we eventually would see Napoleon in Torbay. Following his 1815 defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, the Emperor surrendered to the British and had the opportunity to view our fair shores from the deck of HMS Bellerophon on his journey to his St. Helena exile.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon