There’s an old story that tells of how a sheep hanged a local thief.

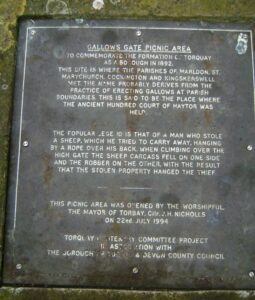

You can read all about the supposed incident up at Gallows Gate where there’s a plaque which recounts:

“Gallows Gate Picnic Area. The popular legend is that of a man who stole a sheep, which he tried to carry away. Hanging by a rope over his back when climbing over the high gate the sheep carcass fell on one side and the robber on the other with the result the stolen property hanged the thief.”  There’s even a gate to be seen. It, however, is a relatively recent addition, a stage-prop for the allegory, a gate to nowhere.

There’s even a gate to be seen. It, however, is a relatively recent addition, a stage-prop for the allegory, a gate to nowhere.

So, did it really happen and when did it supposedly take place?

It’s a nice story but has one major flaw. We’re not alone in telling the tale. There are around thirty places in England with a place called Gallows Gate, or a large boulder called the Hangman’s Stone

They all tell a similar tale.

A sheep-stealer was carrying a live sheep home with its legs tied together, when he stopped to rest against the gate or a boulder; the restless ruminant slipped and struggled, causing the rope to twist round his neck and strangle him. Fate therefore made sure that he would be hanged for his crime.

What we’re reading here is a legend. Legends often centre on a specific place, person or object, the aim being to hand on accounts of events alleged to have occurred. They are generally recounted for entertainment value with the legend almost always brief as it’s normally told in casual conversation. The objective is to explain, warn or educate. Why they are of interest is that they reflect the beliefs, morality and concerns of the community at a particular time.

And this story goes back a long way.

And this story goes back a long way.

The earliest British record of the ‘sheep hangs man’ legend is in Thomas Westcote’s ‘A View of Devonshire in 1630’ (written in 1845), referring to Combe Martin in North Devon. Other sites include Boxford (Berkshire), Hampnett (Gloucestershire), Rottingdean (Sussex) and Barnborough (Yorkshire). In Allandale (Northumberland) the boulder is called the Wedderstone (from ‘wether’ or ‘castrated ram’), and there is a cautionary rhyme: “When ye yearn for a mutton bone, Think on the Wedderstone”.

The story also seems to change depending on what animal is most prevalent, and worth stealing, in the local area. For example, the first apparent telling comes from 1560 in Klettgau in Switzerland, though this was a pig rather than a sheep. In Charnwood in Leicestershire, it’s a deer.

In Devon there are nine stones with similar hanging legends, with five being on Dartmoor. The tale on the Moor seems to be associated with ‘hangingstones’ which acquired their names from the ‘hanging’ ceremony during a parish beating of the bounds. This was an initiation for young boys attending their first drift when animals are rounded up from the commons in the autumn. A halter would be placed around the boy’s neck and attached to a rock outcrop, leaving the boy suspended for a time with just his feet touching the ground below. Even on Dartmoor, the hanging stones were often located on parish boundaries and associated with nearby gallows. We see the same setting in Torquay.

In Devon there are nine stones with similar hanging legends, with five being on Dartmoor. The tale on the Moor seems to be associated with ‘hangingstones’ which acquired their names from the ‘hanging’ ceremony during a parish beating of the bounds. This was an initiation for young boys attending their first drift when animals are rounded up from the commons in the autumn. A halter would be placed around the boy’s neck and attached to a rock outcrop, leaving the boy suspended for a time with just his feet touching the ground below. Even on Dartmoor, the hanging stones were often located on parish boundaries and associated with nearby gallows. We see the same setting in Torquay.

In our part of the world the legend reflects the importance of sheep farming. It especially serves to warn against sheep stealing. The message was that even if the Law didn’t punish you, then God would.

In our part of the world the legend reflects the importance of sheep farming. It especially serves to warn against sheep stealing. The message was that even if the Law didn’t punish you, then God would.

A shortage of food was common, particularly during the winter, and one sheep could feed a family for a month. But sheep were easy prey, more compliant than cattle, a good size and often left in open fields. They yielded valuable meat, tallow, fat and skin, for sale or for use at home. Also, once converted to mutton, pilfered ruminants are difficult to identify. Hence, theft appears to have been commonplace and the story may also telling us that a lot of thieves were getting away with their crime, despite the efforts of the authorities and the severe penalties.

We may be seeing evidence of social change. The growth of towns such as Torquay was introducing a new kind of criminal to prey on rural folk. Good country neighbours had long-established traditions of mutual support. They would never steal from one another as they know that the loss of a single animal could lead to the death of an entire family. The story then suggests that the thief was an outsider and an idiot, a farm hand would know how to handle rope and not make such a simple mistake. Accordingly, this may be a yarn told by country people about thieving townies.

The location of the story, by Torquay’s place of execution, is significant. It was a place where justice was seen to be done. Death by rope, either by man or by God.

The location of the story, by Torquay’s place of execution, is significant. It was a place where justice was seen to be done. Death by rope, either by man or by God.

This is a very ancient place. The Haytor Hundred is recorded as being held at Kingsland (the King’s Land). This would have seen gatherings of men called to fight and hold open air courts, as well as providing a good lookout for sighting hostile ships in the Bay. The partition of Devon into Hundreds dates from King Alfred (871-901) and so this indicates that Gallows Gate served for well over a thousand years as a place of execution. A lot of folk lost their lives on that Torquay hilltop.

Hanging has been the principal form of execution in Britain since the fifth century, with even children as young as seven being sent to the gallows. Sir Samuel Romilly, speaking to the House of Commons in 1810, declared that “There is no country on the face of the earth in which there have been so many different offences according to law to be punished with death as in England.”

Many of these offences were introduced to protect the property of those wealthy classes that had emerged during the first half of the eighteenth century. It was intended that the law should act as a deterrent. People would not commit crimes if they knew that they could be sentenced to death. This was also the reason why executions were public spectacles until the 1860s. Justice needed to be seen to be done and so criminals were left to rot at execution sites. An additional moral lesson about God’s justice wouldn’t do any harm.

In 1723 The Black Act created fifty capital offences for various acts of theft and poaching. Following that precedent, capital punishment legislation proliferated in a haphazard manner to deal with individual crimes as they arose. Effectively, the rich made the laws to protect their interests so anything that threated their wealth, property or sense of law and order was criminalised and made punishable by death.

In 1723 The Black Act created fifty capital offences for various acts of theft and poaching. Following that precedent, capital punishment legislation proliferated in a haphazard manner to deal with individual crimes as they arose. Effectively, the rich made the laws to protect their interests so anything that threated their wealth, property or sense of law and order was criminalised and made punishable by death.

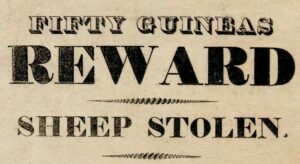

This became known as the Bloody Code which, over time, imposed the death penalty for over two-hundred offences. These included: stealing from a rabbit warren; writing a threatening letter; pickpocketing goods worth a shilling; being an unmarried mother concealing a stillborn child; wrecking a fishpond; “being in the company of Gypsies for one month”; “strong evidence of malice in a child aged 7–14 years of age”; and “blacking the face or using a disguise whilst committing a crime”. In 1741 came a specific law entitled, ‘An Act to render the Laws more effective for the preventing the stealing and destroying of Sheep’. This was a time of rural hunger, high prices and escalating temptations for the starving. In response, the legislation explicitly identified the death penalty for the increasing incidence of rustling.

In 1741 came a specific law entitled, ‘An Act to render the Laws more effective for the preventing the stealing and destroying of Sheep’. This was a time of rural hunger, high prices and escalating temptations for the starving. In response, the legislation explicitly identified the death penalty for the increasing incidence of rustling.

We don’t know the exact number of hangings for that offence. However, between 1825 and 1831 alone 9,316 death sentences were passed in Britain, 1,039 for sheep-stealing. We do know that this was a largely male occupation. Between 1735 to 1799 only five women were executed for stealing sheep or horses across the whole of England.

But not all the convicted were hanged. Whilst executions for murder, burglary and robbery were common, death sentences for minor offenders were often not carried out. Between 1770 and 1830, for example, an estimated 35,000 death sentences were handed down in England and Wales, of which 7,000 executions were actually carried out.

But not all the convicted were hanged. Whilst executions for murder, burglary and robbery were common, death sentences for minor offenders were often not carried out. Between 1770 and 1830, for example, an estimated 35,000 death sentences were handed down in England and Wales, of which 7,000 executions were actually carried out.

There were, by then, alternatives to the death penalty. These were imprisonment and transportation. Following its introduction as a formal sentencing option in 1718, transportation had quickly come to dominate the courts’ sentencing practices. Nevertheless, attitudes temporarily grew harsher at times of societal stress, such as in the early 1780s following the transportation crisis created by the American War, and then during the panic about rising crime rates that followed demobilisation in 1782.

Execution rates also varied greatly in different parts of the country. In the regions around London there was a much higher use of capital punishment compared to places further away, such as in the South West. The exception was Devon where we still liked to hang folk for minor offences.

Execution rates also varied greatly in different parts of the country. In the regions around London there was a much higher use of capital punishment compared to places further away, such as in the South West. The exception was Devon where we still liked to hang folk for minor offences.

As the nineteenth century progressed the numbers of executions fell. In 1831 only 162 persons were sentenced to death for sheep-stealing in England and Wales, with a single execution being carried out. This was around the time that Torquay’s Gallows Gate seems to have been relocated away from its prominent hilltop position. Tourists just didn’t want to see rotting corpses hanging on the skyline overlooking a modern town.

It was not until 1832 that sheep, cattle, and horse stealing, along with shoplifting, were removed from the list of felonies for which you could end up at the end of a rope.

It was not until 1832 that sheep, cattle, and horse stealing, along with shoplifting, were removed from the list of felonies for which you could end up at the end of a rope.

By then it was largely recognised that there were problems in having such a wide range of capital offences. Offenders were more likely to resist arrest, witnesses were being dissuaded from coming forward, and some jurors were less likely to convict. Indeed, the lessons we learnt from the enactment of the Bloody Code are worth remembering today.

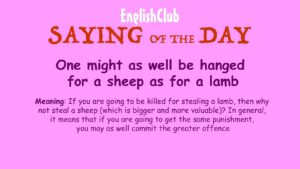

There was also the unintended consequence that the Bloody Code even encouraged greater crimes. Back in 1678 John Ray’s collection of English proverbs identified the problem: “As good be hang’d for an old sheep as a young lamb”. We still use the saying today.

There was also the unintended consequence that the Bloody Code even encouraged greater crimes. Back in 1678 John Ray’s collection of English proverbs identified the problem: “As good be hang’d for an old sheep as a young lamb”. We still use the saying today.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon