Torquay grew rapidly during the nineteenth century: in 1801 there were 838 persons; by 1851, 11,474; and by 1901 it was 33,625 – though this now included St Marychurch and Cockington. Alongside this growth, Torquay’s reputation as the richest town in England meant that the faith of its inhabitants mattered across the nation. It was this advance, display and diversity of the town’s Christian tradition that created the Torquay townscape as we know it today.

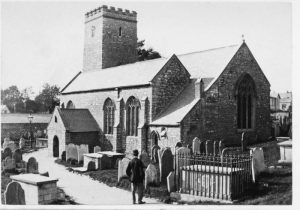

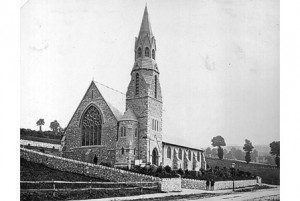

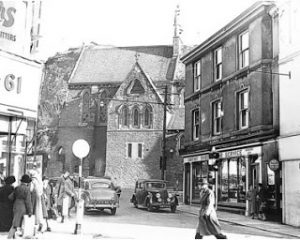

Torquay had, since the Reformation that closed down Torre Abbey, been staunchly Anglican. Many Victorians believed that Britain’s prosperity, liberty and Empire were rooted in the Protestant faith – and in the early years of the nineteenth century this was expected to continue. Indeed, Torquay’s Anglican churches were popular, expanding and reforming, while old local churches were being restored (such as St Savoiur’s pictured above) and any clerical abuses were being tackled. New Anglican churches were being built: St John the Apostle, in 1822; St Mary Magdalene in 1849; St Matthias, Ilsham in 1857; St Luke’s in 1861; All Saints, Babbacombe in 1865; All Saints, Torre in 1867; Christ Church, Ellacombe in 1868 (pictured below).

Yet, there were indications of challenge and change as the Church of England struggled to maintain its influence over the people of the town.

The primary cause for Establishment concern was the growth of Catholicism.

Catholics had long been discriminated against in England and had only been given religious toleration, alongside Protestant Nonconformists, in 1828. There had long been Catholic families in the Bay- the Carys of Torre Abbey, for example – but in 1850 the Pope introduced a network of Roman Catholic bishoprics across England. The first Catholic Bishop of Plymouth took up his new office in 1851 when there were already nine Devon Catholic congregations, one being in Torquay. Such an increase in Catholic worshippers was largely due to an influx of people from other parts of Britain. They worshipped at the Assumption of Our Lady, built in 1853; and Our Lady Help of Christians & St Denis (1867).

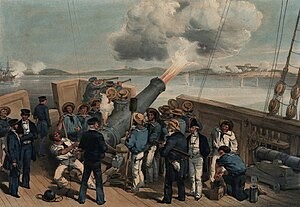

This new manifestation of faith didn’t go down well with the bellicose Anglican Bishop of Exeter Henry Phillpotts (pictured above) who from 1830 to 1869 ruled a diocese which ran from Land’s End to the east of Devon. In 1851 he announced, “The Bishop of Rome hath taken upon himself to name the Town of Plymouth in the Archdeaconry of Totnes, we declare that the said appointment is manifestly schismatic and void.” Incidentally, Henry’s home was on the site of the Palace Hotel, he laid out Bishops Walk, and is buried in the churchyard at St Marychurch.

There is an apocryphal story that the Catholic Church of the Assumption of Our Lady was originally going to be built on Sheddon Hill. However, the town’s elite didn’t want to have an imposing Catholic Church being seen by those approaching Torquay from the sea, and so St Luke’s was built on a nearby site – a kind of ecclesiastical chess to maintain Anglican dominance of the skyline. However, the Catholic Church of the Assumption of Our Lady was built in 1853, while St Luke’s wasn’t built until 1861. Nonetheless, that the story was being told and believed does suggest the level of competition between traditions at the time.

The Anglican Church was also concerned about the growth in Nonconformist churches. Across the world Protestantism was diverse, without structural unity or central human authority, and it was the same in Torquay as many other traditions emerged, and splits and theological disputes occurred.

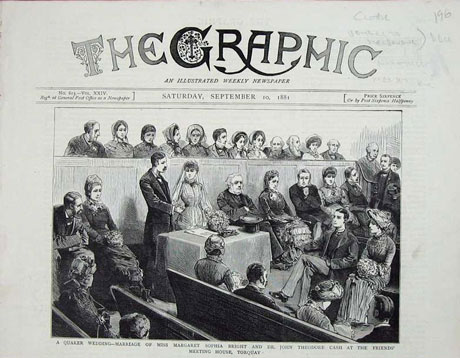

In Devon in 1851 there were 142 ‘dissenting’ denominations, including Torquay’s: Furrough Road United Reformed Church, 1852; Upton Vale Baptist Church, 1832; and the Quaker meeting house, based in a variety of locations from 1840 onwards. The current Quaker meeting house is pictured below.

To take one example, the old chapel off Fleet Street – now a cafe and once Blu Cargo Canteen Bar and the Piazza – was built as the Salem Chapel in 1839 and was the church of a sect known as the Starkites. Their charismatic leader was Robert Stark who in 1814 decided that humanity was totally depraved and corrupted. As they held that Scripture had the final authority, their 250 members spent a great deal of time reading the Bible and trying to convert everyone else. The Starkites also had a fondness for disrupting the meetings of other rival local traditions, such as the Millerites. The Starkites are long gone, though Torquay’s Millerites – in their new incarnation as Adventists – are still going strong in Torquay.

A Torquay Quaker wedding in 1881

Across Devon in 1851 there were 223 Methodist chapels and preaching houses – Victoria Park Methodist Church was built in 1864.

There were also the Plymouth Brethren, a group of independent congregations which emerged in 1830. One member of the Brethren was St Marychurch naturalist Philip Henry Gosse (pictured below) who became the Brethren’s pastor and overseer of the Brethren meetings. At first, the meetings were held over a stable, but then in finer quarters, which Philip may have financed himself.

Philip’s “considerable missionary zeal” caused him to refuse to use the ‘St’ in St Marychurch and so he gave his address as ‘Torquay’ so as not to have anything to do with the “so-called Church of England”. He also gave money to charity, especially to foreign missionaries, including ones sent to the “Popish, priest-ridden Irish.”

Such dissent wasn’t confined to disagreements about the finer points of theology, however. In 1888 rioting and a hundred jailings followed the Salvation Army’s demand to be allowed to march on a Sunday on the streets of Torquay. The Army won their campaign indicating that times were changing and that the control exercised by the town’s religious and secular elite was waning.

St Luke’s

While Torquay had Jewish visitors and residents – including Benjamin Disraeli, who had Italian-Sephardic Jewish ancestry – the only non-Christian Devon faiths with places of worship were the two Jewish synagogues in Exeter and Plymouth, each having less than 50 members in 1851. However, non Christian groups would emerge in the later nineteenth century – such as the Theosophists.

One of the impressions we have of Victorian Torquay is of a deeply religious society. Yet, it’s estimated that just under half of the Devon population attended church. Across the nation the churches had largely failed to maintain the support of the urban working-class, and by 1900 they were beginning to lose the allegiance of the respectable middle-classes too.

This decline was reflected in Torquay. In 1895 the Vicar of Ellacombe, the Reverend CE Storrs, gave a sermon entitled, “If Christ came to Ellacombe”. The Reverend believed that Jesus would be very displeased at what he would find in urban Torquay: “If Christ came to Ellacombe he would see indifference and unbelief more than ever He suffered on earth before. He would find the evil of intemperance rampant. He would meet it everywhere. He would see drunken crowds and sottish selfishness.”

St John’s

In the following months research was undertaken amongst, “the working men as a class” to find out why they weren’t going to church. Women, it was decided, weren’t the problem. They were retaining their church-going habits as, “it was more of change for women to go out on a Sunday, because they had been in all week, where the men had not”.

A public meeting was then held to dig deeper into why local men just weren’t going to church as they were expected to by both the local clergy and Torquay’s wider Establishment. At the meeting, the top 10 reasons for not attending church given by residents were read out. Some said that they did not care to attend a church that had one part for the rich (where seats could be bought) and another for the poor, or that men and women were divided up. Some claimed that the sermons were too long, too dull and too dry. Other reasons included, “the great need for fresh air” and that working men had unsuitable clothes for church.

Above all, the researchers found that amongst the men of Torquay there was an “indifference to religion”. The meeting further reported that, “some weren’t Christians” at all and, “a great reason in large centres of population for men not going to church was the spread of atheistic doctrines”.

Upton Vale

And that decline in church-going and religious affiliation has continued. In 2019 52% of the public say they do not belong to any religion, compared with 31% in 1983. The number of people identifying as Christian has fallen from 66% to 38% over the same period. Only 1% of people aged 18-24 now identify as Church of England while one in four members of the public are atheists, compared with one in 10 in 1998.

Nevertheless, Torquay’s Christian communities – now alongside 23 non-Christian local faiths and beliefs – continue to strive to make the Bay a better place.

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us