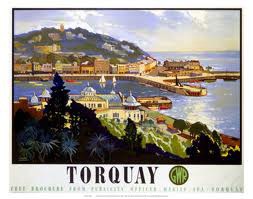

While it was the visiting wives and relatives of naval officers that initiated Torquay as a tourist town, it was the Napoleonic wars that really led to the town’s rapid growth. The rich, denied their visits to continental Europe, were compelled to find leisure closer to home and so Torquay grew into a premier health resort. From a small fishing village of 838 in 1800, 50 years later Torquay’s population stood at 11,474. Thousands more would visit depending on the season.

Along with the many attracted by opportunities for employment, Torquay also became the home of those who lived on the very edges of society – the criminal, the homeless, the vagrant, the addicted, the prostitute and the long-term unemployed. Collectively these people eventually became known as the underclass and seen as a separate type of person, who behaved not just differently to working and middle class folk, but to other poor people as well.

Most vulnerable were the very young and poor – at least adults in Torquay had some power. Many local children were ruthlessly exploited or even murdered. At Lowe’s Bridge on the Newton Road lived the baby farmer Charlotte Winser. On February 15, 1865, the body of Mary Jane Harris’ illegitimate four-month-old son was found beside the road wrapped up in a copy of the Western Times. Harris had farmed out the infant to Winsor for 3 shillings a week. At first she had resisted Winsor’s offer to dispose of the child though, when the burden of his support became too much, she stood by and watched Winsor smother her son. Testimony revealed that Charlotte Winser conducted a steady trade of boarding illegitimate children for a few shillings a week or “putting them away” – killing them – for a set fee of £5.

The combination of dangerous working conditions and long hours meant that children were worked as hard as any adult, but without laws to protect them. In 1900 a deputation on the matter of child labour visited Torquay Council. It was led by local churchmen from Upton and St Luke’s who raised the issue of, “children at a very early age subjected to heavy and laborious work, and more particularly to the late hours at which they were employed”. The Chief Officer of the Coastguard was interviewed and he said that he had rejected for service around half of the Torquay boys who had applied to join. They had bad teeth or poor eyesight, while a third suffered from varicose veins, believed to be caused by long standing and strain.

One accepted characteristic of those at the margins was criminality. Yet Torquay was too small for a class of professional criminals to remain inconspicuous. What thieves and swindlers we had preyed on their poverty stricken neighbours rather than the gentry. Indeed, Torquay’s police had a reputation for coming down remorselessly on those who threatened public order in general and the affluent in particular.

During Torquay’s early years, lanterns and candlelight were the sole sources of illumination but on October 8th 1834 the darkness was banished. Forty gas lamps were installed in our main thoroughfares – two years later the light extended from Castle Circus to Torre. Yet illumination was the privilege of the upper and middle classes while the poor, uneducated and criminal inhabited a different social world of raw sewage and cholera in Swan Street, George Street and Pimlico. Street lighting gentrified the commercial centre of Torquay but relegated other areas, the intense pools of light emphasising the darkness beyond and the dangers it concealed: “Oh! And may it prosper, may it show, The ruffian as he lurks, And may the new light drive away, The Devil and his works,” wrote a Torquay poet at the time.

Begging was another annoyance experienced by both residents and visitors. In 1904, the Torquay Charity Organising Society instituted a campaign to “elevate the deserving poor by suppressing the haphazard harmful charity existing in Torquay”. The COS complained that “By tramping around the hills and pulling the bell at the doors of villas, a man or woman could receive any amount of half-crowns”.

However, despite the COS’ efforts, indiscriminate charity clearly continued. In 1911, they reported that tramps and beggars, “still present one of the most difficult problems in Torquay”. In response, they produced a leaflet to discourage “rich people on the hills” from giving to vagrants.

The presence of the homeless and the beggar continued, as it does today. Yet it changed in character with the social upheavals of the 1960s. In September 1964 the President of Torquay Trades Union Council complained that, “I did not think that in the twentieth century we would have people who would walk about literally stinking.” The unions went on to condemn, “Bohemians and their unhygienic habit of sleeping rough on the beaches, and lounging on street corners, wearing al fresco attire and no shoes and ganging together to block pavements to pedestrians. The holiday season had always attracted a small number of the begging fraternity… now there were more requests from unshaven shabbily dressed and unwashed gentlemen for the price of a glass of coffee. They sleep under the stars or under carefully-erected Corporation deck chairs, the Beacon Quay car park or on the tow path seats flanking the harbour.”

These new arrivals focussed attention on what we now see as the main indicator of membership of Torquay’s underclass – the use of alcohol and illegal drugs. Drunkenness was always of great concern, with the related loss of self-control particularly associated with the lower classes. Along with ongoing disorder in and around Torquay’s pubs and beer houses, drink was linked with riots in the town in 1847, 1867 and 1888. Our love affair with alcohol was often remarked on by outsiders. When the Canadian Isabella Cowen visited Torquay in 1892 she noted that many of us drank with the sole intention of getting drunk and that public insobriety was more or less accepted. She was deeply shocked by Torquay’s, “men and women whose bleary eyes and blotched complexion betray their liking for the inebriating cup. As long as an Englishman can keep upon his feet he is considered quite respectable.”

This social problem generated a response in 1834 when the Torquay Temperance Society was launched, the campaigners being joined by “Bands of Hope, good Templar Lodges, local branches of the Church of England Temperance Societies, and parochial Temperance Guilds”. A series of British Workman Public Houses were then opened, “where refreshments of all kinds can be had, but no intoxicating liquors”. The first was in Union Street in November 1872, followed by Vaughan Parade – for the benefit of fishermen and sailors – and then Market Street.

The campaign against drink continued but old habits persist. Today Torbay has one of the highest proportions of alcoholics receiving benefits in England – the fifth highest in proportion to population of any primary care trust in England.

And the use of narcotics was not a new phenomenon, there being more ‘hard drugs’ in Torquay in the nineteenth century than any time before or since. An estimated 5 out of 6 working class families used opium on a regular basis with many of Torquay’s famous residents and visitors freely using a variety of drugs that are illegal today. But opium was respectable as it was the standard medication for almost everything – the Victorian version of aspirin – and patent opium products were openly dispensed by physicians directly to patients by prescription.

On the other hand, it has been suggested that a significant change in drug use came with the growth of Torquay’s counter culture. In the early 1960s the original Torquay beatnik pub was The Melville Inn (now the Clipper Inn), focus of the alternative music and poetry scene – the most famous product of which was Donovan who lived on Abbey Road. Local writer and poet Mike Williams was there and has charted the rise and fall of a generation. He remembers, “The beatnik lifestyle was mainly one of part-time work, the cheapest possible rented rooms, support from the National Assistance Board, and loafing about on beaches and in pubs. The end of the beatnik period can be dated absolutely: to the ‘Wholly Communion’ poetry gig at The Albert Hall in London in the autumn of 1965. Beatnik was dead, hippy was in, and the innocence and joy of being young in Torquay was lost forever. Mandrex, LSD, and heroin took a hold. There are still ‘acid casualties’ walking around Torquay to this day.”

The growth of the town’s alternative youth culture was quickly noticed by the authorities. In early 1969 Torbay’s Police issued a statement saying they were keeping an eye on “local hippies” – a Paignton chemist had been burgled and a large amount of drugs was stolen, it was assumed for resale. South Devon’s pub landlords were warned to be on the lookout for anyone smoking “oddly shaped cigarettes”. Pharmacists were similarly encouraged to be wary of customers who appeared to be either, “dozy, dirty, nervous, irritable or just not quite right”. Many local pharmacies then refused to supply a number of products to “suspicious characters”.

At 9.30pm on April 12, 1969 around 70 members of the Torbay Drugs Squad and other officers made a drugs raid on the adopted pub of Torquay’s hippies, Belgrave Road’s Rising Sun Inn, with a warrant to search anyone. This was the first raid of its kind in Torbay. Some 17 people were arrested – 16 for possession under the Dangerous Drugs Act and one for wilfully obstructing Police Constable James Copeland.

The conflict between the hippies and the authorities continued. In March 1970 an anonymous 21-year-old spokesman for the town’s resident flower children claimed that the police were harassing them in order to break up their community before the influx of summer visitors. He said his flat had been raided and that police were putting pressure on landlords to turn him and his friends out of their homes. He asserted, “They are also tightening up on the places where we meet – trying to get them to close down or to refuse to serve us. They are using the stop-and-search powers more. They’ll stop anyone who dresses differently or who has long hair. They’re really leaning on the communities.” Mutual hostility would come to a head in a riot in 1972 when Torquay’s Police Station was attacked.

The challenges posed by local drug use continue – in 2013 the chairman of Torbay Council stated that 520 “problem drug addicts were costing the Bay’s taxpayers around £2million in treatment and support”.

For destitute women in nineteenth century Torquay there was always one way to avoid starvation. For well over a century prostitutes could be found at night frequenting harbour pubs and Cary Green – the area in front of the Pavilion. Though prostitution was common throughout England, Torquay had its unique characteristics. We claimed to be the wealthiest in England and the affluent needed a large, mostly female, servile class – in 1871 there were 12,772 females to 8,885 males in Torquay. If any of those women, many from Devon’s villages, couldn’t find work, there was often only one alternative.

A nineteenth century town commonly had 1 prostitute per 36 inhabitants, or 1 per 12 adult males. If we take the above ratios, this would give us hundreds of Torquay prostitutes. Generally, their activities were ignored and rarely commented on… unless they attracted the attention of the authorities or reached the courts. In 1853, for instance, Torquay’s Chief Constable Charles Kilby complained of the “unbecoming manner that young women of the town wander around the thoroughfares without bonnets and shawls”.

When prostitution became too blatant it was suppressed. In 1899 the landlord of the Abbey Inn on Abbey Road was charged with allowing his pub to be used as “a habitual resort of women of ill-fame”. A Detective Thomas watched the Inn on the night of March 12 between the hours of 8 and 11 and later told the court. “He saw women of loose character enter. They stayed for a considerable time – between 10 and 25 minutes. They entered and returned several times on the same evening, sometimes alone and sometimes in company with men… Entering the Inn, he saw three loose women in one of the rooms.” Unaccompanied women of good character were unlikely to visit an inn and so evidence of impropriety included a notice instructing females not to remain in the house for more than a quarter of an hour. On one occasion the detective heard the landlord shout: “Time, Ladies!” indicating that women were not being escorted by a man. While being cross-examined, Detective Thomas said: “There is nothing to distinguish them from others except their bad language. The house was a quiet one and perhaps was not likely to attract women of the town in pursuit of their vocation.” The landlord was fined and the brewery took away his tenancy.

For the truly impoverished there was the workhouse, though Torquay preferred to export its perceived problems. The Newton Abbot Poor Law Union was formed in 1836 and their workhouse, which could accommodate 350 inmates, was built in 1837 in East Street – around where the new Sainsbury’s is now. The desperately poor of all ages, the mentally ill and disabled were, for decades, transported out of Torquay to a place where they would not offend tourist sensibilities. Effectively, our most vulnerable were sent away, hidden from view and forgotten. Workhouses were made deliberately unwelcoming and harsh – they needed to be as conditions were so awful for many people in the Bay with disease and starvation commonplace. Workhouses had to be seen as a very last resort and so even the starving and dying avoided them. Not surprisingly abuse was common and there was a terrible scandal at Newton Abbot Workhouse in 1894. By the time of a Torquay Times visit in 1928, it was called the Newton Abbot Union Institution – the term workhouse had by then become tainted. The newspaper’s correspondents reflected society’s view that the very poor should be punished as well as supported. They wrote, “The pauper suffers in a general sense for the improvidence of which he has been guilty, exactly as a criminal expiates his wrong doing behind bars.”

These “inmates” had their freedom tightly restricted. The correspondents noted that, “What hurts the bulk of the inmates is the confinement. There are some inmates who very rarely, if ever, go outside the walls… With some of them melancholia is engendered, and eventually become anything but normal. The tempers become deranged.” In effect, if you didn’t have a mental illness before you entered the workhouse, you would soon acquire one. Workhouses were only officially abolished by the Local Government Act of 1929, but many persisted into the 1940s.

Outside of the workhouse the impoverished and unemployed turned to charity. In 1895 the charitable Torquay Mendicity Society estimated that, “There are at least 200 men who have no work to do, and many of them have wives and families dependent upon them. The districts feeling the pinch most are Ellacombe, Torre, Upton and Melville Street. Amongst the fishermen too, great distress prevails. The Market Corner has been a kind of barometer by which one can tell the condition of the labour market and large numbers of men, anxious and willing to work, if they could get employment, have assembled there.”

In February of 1895 a correspondent from the Torquay Times visited a soup kitchen in Market Street. He described how soup was given out to 500 local people. He reported, “And now Mrs Gibbs and Mrs. Wreyford, with turned up sleeves and armed with large enamelled cups, mount guard… Then arrived the children, some with milk cans, some with milk jugs, and some with even washstand jugs. And now the crush has become so great. An old man leaning tremulously on a stick is seen approaching the table. Here comes an old lady who is bewildered by the rush. Then come the mothers, some respectably clad, and evidently experiencing that mortification at receiving charity with which we can all sympathise, and others with torn garments and dishevelled appearance”.

The creation of the welfare state after the Second World War alleviated the worst of the poverty in Torquay. We no longer witness starvation or child labour, and street prostitution has largely disappeared. Those seen as being from the underclass remain, however. The nature of poverty changes and the latter years of the twentieth century saw economic polarisation increasing. The causes included a shift from a goods-producing to a service-producing economy, the offshore outsourcing of labour and increased automation. Our modern underclass now consists of the insecure self-employed, part-time and low paid workers, the bankrupt, the homeless, and the long term unemployed. As always drugs and alcohol play their part. Debate continues over whether the new poor are so detached from society that they constitute a separate social class… or whether some people have simply too little money and hope to be able to share in everyday life with the rest of the population.

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon. Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share? Contact us