Between the communities of Torbay and the city of Exeter are the Haldon Hills. This ridge of high ground, the highest point being around 820 feet, is a land of ancient battles, shallow graves, suicidal deer, irritable commuters, broken down campervans and doggers.

And from the period from the Restoration in 1660 to around 1800 it was the haunt of the highwayman, a breed of rural armed criminal that were described as being “as common as crows” across the whole of rural England.

And from the period from the Restoration in 1660 to around 1800 it was the haunt of the highwayman, a breed of rural armed criminal that were described as being “as common as crows” across the whole of rural England.

Violent crime was a part of life in post-Civil War England. Footpads ambushed travellers on foot but highwaymen were a breed above, usually robbing on horseback. Mounted villains were, of course, more affluent and so considered to be socially superior, giving them a higher status in the world of the seventeenth and eighteenth century criminal.

Travel across Devon was already hazardous due to the lack of decent roads, and outside of towns and villages few rode alone without fear of being robbed. As a wise precaution, people often joined together in groups or hired escorts.

Indeed, rural robbery was so common that it was said that, “We English always carry two purses on our journeys, a small one for the robbers and a large one for ourselves.” Other prudent travellers collected counterfeit money and offered it on demand; while some had boots made with cavities in the heel for their valuables or relied on secret pockets.

While much highwayman history has faded into legend, we know from trial reports that they did use phrases that are still remembered today: “Stand and deliver your purse!”; “Stand and deliver your money!”; “Your money or your life!”

Coaches were particularly vulnerable as they travelled slowly on poorly constructed roads and often lacked good protection. Few could afford to travel by coach so any passengers were conspicuously affluent themselves or likely to be transporting valuables for others. Another easy target were the postboys who carried the mail.

Coaches were particularly vulnerable as they travelled slowly on poorly constructed roads and often lacked good protection. Few could afford to travel by coach so any passengers were conspicuously affluent themselves or likely to be transporting valuables for others. Another easy target were the postboys who carried the mail.

Such was the prevalence of rural robbery that in 1692 an ‘Act of Parliament for the Apprehending of Highway Men’ established a monetary reward for the capture of highwaymen, and immunity to those who gave away their accomplices.

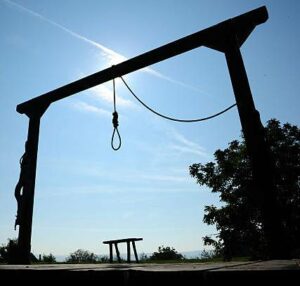

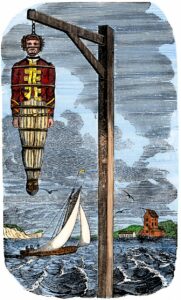

The penalty for robbery with violence was hanging, with bodies left to rot on gibbets as a warning to others. Many highwaymen would then have ended their lives at the end of a rope at Galmpton’s Windy Corner, Torquay’s Gallows Gate, or Newton Abbot’s Forches Cross.

The penalty for robbery with violence was hanging, with bodies left to rot on gibbets as a warning to others. Many highwaymen would then have ended their lives at the end of a rope at Galmpton’s Windy Corner, Torquay’s Gallows Gate, or Newton Abbot’s Forches Cross.

Yet this was a Devon with a lack of governance and with no organised provision to police the highways. And there was often no clear divide between the criminal and the law-abiding; it was suspected that some innkeepers and ostlers were passing on information to the highwaymen. Across the county there could be lawless hamlets which preyed on travellers as a local industry, the community protecting the predators in their midst. This seems to be in much the same way that South Devon’s smugglers received the support of local folk, so avoiding detection and arrest, with convictions consequently being difficult.

Yet this was a Devon with a lack of governance and with no organised provision to police the highways. And there was often no clear divide between the criminal and the law-abiding; it was suspected that some innkeepers and ostlers were passing on information to the highwaymen. Across the county there could be lawless hamlets which preyed on travellers as a local industry, the community protecting the predators in their midst. This seems to be in much the same way that South Devon’s smugglers received the support of local folk, so avoiding detection and arrest, with convictions consequently being difficult.

Some highwayman did gain notoriety, usually losing their lives on the gallows, and it is here that we have a record of their activities; and where we can see how they acquired their legendary status. In particular those that were executed in good spirits or showing no fear seem to have been admired by many of the people who came to watch. However, such narratives mostly come from places with an established print industry, or were linked to political causes such as those in Ireland or Scotland. Devon had neither a system of printing or distribution of sensationalist ‘broadsides’, or of a nationalist or Jacobin underground.

As highway robbery in Devon was commonplace and unglamorous, most incidents remain unrecorded. It is only later – once the constant threat had receded – that we see the highwayman being glamorised as a folk hero.

As highway robbery in Devon was commonplace and unglamorous, most incidents remain unrecorded. It is only later – once the constant threat had receded – that we see the highwayman being glamorised as a folk hero.

We do have a local example in the career of Jack Witherington.

Jack preyed upon the coaching route that ran between Chudleigh and Ashburton. As with other highwaymen he had fought in the Civil Wars. He was finally captured by the militia at Malmesbury after staging another robbery and was hanged at London’s Tyburn on 1 April 1691. If the trial and hanging had taken place in Devon it is unlikely that we would have ever have heard of him.

During his appearance before the court it was recorded that Jack was given shelter by a family named Cox who lived at Chudleigh’s ‘Rowell’s Farm’ where he hid in the chimney breast to evade his pursuers. This became Chudleigh’s ‘Highwayman’s Haunt Inn’ which closed in 2022.

During his appearance before the court it was recorded that Jack was given shelter by a family named Cox who lived at Chudleigh’s ‘Rowell’s Farm’ where he hid in the chimney breast to evade his pursuers. This became Chudleigh’s ‘Highwayman’s Haunt Inn’ which closed in 2022.

By the final years of the eighteenth century the highwaymen were becoming much less of a threat to travellers. There are a few suggested reasons for this.

The unreliable blunderbuss was being replaced by repeating handguns which, as the highwaymen complained, travelling folk were very willing to use. We also see an expansion of turnpikes and gated toll-roads allowing faster coaches and making it more difficult for bandits to move around unobserved. The Inclosure Act of 1773 had in many places led to the building of stone walls on both sides of roads so reducing opportunities for ambush. Perhaps most significant were rapid population increases and more social mobility that eroded the insularity and remoteness of much of Devon.  Or it could just be that untraceable gold and silver coins were being replaced by identifiable banknotes which could be more easily concealed, and by cheques that couldn’t be converted to cash.

Or it could just be that untraceable gold and silver coins were being replaced by identifiable banknotes which could be more easily concealed, and by cheques that couldn’t be converted to cash.

Travelling was certainly becoming safer, the roads were busier, once isolated Devon villages were growing, and old community loyalties were eroding. Devon was no longer a lawless rural backwater and was fast becoming part of a modern England.

The highwayman then found himself engaged in a much riskier and less lucrative profession. As a consequence, during the eighteenth century there were only four really famous highwaymen to be found across the nation: Dick Turpin, Claude Duval, Captain McLean and Jack Rann.

After 1815 mounted robbery across England was rare with the last recorded incident taking place in 1831. Highwaymen relied on quiet roads, unpoliced desolate spaces, being able to outgun their victims, quick profits, and villagers unlikely to inform the authorities. All these prerequisites were already diminishing by the late eighteenth century.

And so the age of the highwaymen came to an end.