The true mothers and fathers of Torbay were never the Georgian gentlefolk we are told about.

Our real forebears were organised and often violent criminals. Their trade was smuggling.

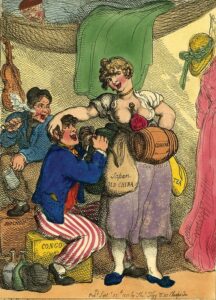

Smuggling was the illegal import of goods in violation of the law. A variety of consumables were far cheaper overseas and so money was to be made if you could bring them in and avoid any import duties or local taxes.

And local smuggling goes back a long way. Way back in the sixteenth century John Leland recorded “thirty hoggesheads of wine in a sellar in Torbay and sugars in quantities not known”.

And local smuggling goes back a long way. Way back in the sixteenth century John Leland recorded “thirty hoggesheads of wine in a sellar in Torbay and sugars in quantities not known”.

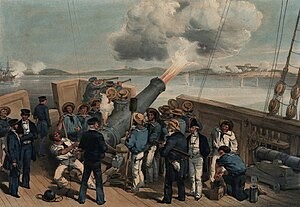

But during the eighteenth century the Royal Navy progressively gained control of the English Channel. Attention then turned to the long-standing practice of smuggling.

This was no minor irritant for the state as a quarter of England’s overseas trade was at the time illegal.

Smuggling could also, on occasion, erupt into violence.

On 12 May 1783, there was a sea battle in Torbay and a mass fight on Paignton’s beach.

On 12 May 1783, there was a sea battle in Torbay and a mass fight on Paignton’s beach.

One side consisted of the Revenue Cutters ‘Spider’ and ‘Alarm’. Facing them were ‘The Swift’, with 16 guns and a crew of 50, alongside a sloop under the command of Thomas Perkinson of Brixham. An exchange of fire between ‘The ‘Swift’ and ‘The Alarm’ took place with the Revenue ships being supported by cannon from the garrison at Berry Head.

On shore a hundred local men were waiting for their consignment of four tons of tea and 9,000 gallons of spirits. During unloading, fighting on the beach ensued with John Stanton, a Cockington smuggler, attempting to kill a Revenue man called Thomas Petheridge, who “was knocked down by a rock and judged likely to lose an eye”. Two other Revenue men escaped, one by hiding under a boat, another by swimming away.

This was just one incident in the long cat-and-mouse game between Torbay’s smugglers and those responsible for dealing with tax evasion.

By the late eighteenth century smuggling had become a massive business. A single cargo on a ship could be worth up to £10,000, the equivalent of £1,800,000 today, with a quarter of all the nation’s smuggling vessels being based in Devon and Cornwall. It was even said that there was so much alcohol coming into the county that people used it to clean their windows.

By the late eighteenth century smuggling had become a massive business. A single cargo on a ship could be worth up to £10,000, the equivalent of £1,800,000 today, with a quarter of all the nation’s smuggling vessels being based in Devon and Cornwall. It was even said that there was so much alcohol coming into the county that people used it to clean their windows.

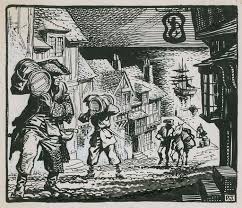

The smuggling was carried out using sailing ships on the sea and horse and carts on land. Contraband was landed across the entire Bay, though by the end of the eighteenth century it was sometimes better to avoid any official observers stationed at Berry Head.

Anstey’s Cove and Oddicombe were consequently preferred, and we have Brandy Cove below Black Head as a reminder of its past use. In Park Road, St Marychurch, there was a small house with a hiding place under the hearth used by smugglers, while Maidencombe Farm and Rocombe Farm similarly had places for concealing barrels of brandy. Other sites include the ancient hollow oak known as ‘The Brandy Bottle Tree’ between Barton Hall and Kerswell Cross, used as a cache by smugglers landing kegs at Watcombe.

Anstey’s Cove and Oddicombe were consequently preferred, and we have Brandy Cove below Black Head as a reminder of its past use. In Park Road, St Marychurch, there was a small house with a hiding place under the hearth used by smugglers, while Maidencombe Farm and Rocombe Farm similarly had places for concealing barrels of brandy. Other sites include the ancient hollow oak known as ‘The Brandy Bottle Tree’ between Barton Hall and Kerswell Cross, used as a cache by smugglers landing kegs at Watcombe.

While the trade offered an escape from poverty, it was also a way to resist an unjust society. Smuggling was a political act as the taxes paid were not for the general social benefit, but for the royal family, England’s wars with France and America, and the ‘occupation’ of Ireland and Scotland. Hence, in a pre-democratic England, avoiding tax was just about the only thing you could do to resist a government you did not agree with.

While the trade offered an escape from poverty, it was also a way to resist an unjust society. Smuggling was a political act as the taxes paid were not for the general social benefit, but for the royal family, England’s wars with France and America, and the ‘occupation’ of Ireland and Scotland. Hence, in a pre-democratic England, avoiding tax was just about the only thing you could do to resist a government you did not agree with.

And this was an activity that involved very large numbers of residents in extensive distribution networks on shore as well as receiving the tacit support from the many welcoming access to cheap goods.

Nonetheless, this was a world of violence, general lawlessness and intimidation. Torbay in particular was known for its large confederacies able to continue their trade without fear.

Indicating the fearsome reputation of the gangs, in December 1760 thirty horses and twenty-five armed men arrived in Exeter bringing in a consignment of tea from the Bay. No attempt was made to disguise their profession and it was well known that “the gang readily resorted to violence”.

Not surprisingly those smugglers that were caught were often not convicted as witnesses could not be found, bribery produced false alibis and with jury men hesitant to send local men to the gallows. Hence, Kipling’s instruction, “Now watch the wall my darling while the gentlemen go by”. That way, bystanders could honestly say they had seen nothing.

Not surprisingly those smugglers that were caught were often not convicted as witnesses could not be found, bribery produced false alibis and with jury men hesitant to send local men to the gallows. Hence, Kipling’s instruction, “Now watch the wall my darling while the gentlemen go by”. That way, bystanders could honestly say they had seen nothing.

It may not be a coincidence that many local ghost stories have their origin in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. This was at the height of the trade. For example, the historian Theo Brown remembers her father saying that nothing would induce anyone to walk from St Marychurch to Shaldon after dark, the road being haunted by the vicious ghost prankster ‘Spring Hill Jack’, where “balls of fire would roll out of the hedges in front of people who ventured there at night”. And in Paignton it was claimed that smugglers used white paint to make their horses look like skeletal steeds.

It may not be a coincidence that many local ghost stories have their origin in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. This was at the height of the trade. For example, the historian Theo Brown remembers her father saying that nothing would induce anyone to walk from St Marychurch to Shaldon after dark, the road being haunted by the vicious ghost prankster ‘Spring Hill Jack’, where “balls of fire would roll out of the hedges in front of people who ventured there at night”. And in Paignton it was claimed that smugglers used white paint to make their horses look like skeletal steeds.

Such stories could well have been put about to discourage folk from venturing outdoors and to explain any odd nocturnal activities.

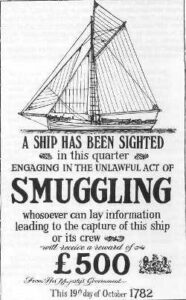

Tasked with eliminating smuggling in the 1780s were teams of preventive officers.

Tasked with eliminating smuggling in the 1780s were teams of preventive officers.

Four Revenue cutters operated between Dorset’s St Albans Head and Berry Head, with individual Customs Officers at Torquay, Paignton, Brixham, Salcombe, Dartmouth and Totnes. However, there were always insufficient resources to patrol the coastline and most smugglers were never caught. And it was often a dangerous occupation for a lone officer on the cliffs at night…

By the early years of the nineteenth century the Revenue Men were becoming better organised on-shore and had more and improved ships. And so the halcyon days of the free traders were coming to an end.

By the early years of the nineteenth century the Revenue Men were becoming better organised on-shore and had more and improved ships. And so the halcyon days of the free traders were coming to an end.

Nevertheless, it was the smugglers, their allies and customers who were the real mothers and fathers of Torbay, and not the latecomer great families we are often told about.