For centuries folk wandering the Bay’s beaches have been discovering unusual bones and stone tools; while, more recently, trawlers have been dragging up the remains of extinct beasts in their nets.

Even way back in 1865 we were finding things. An article by archaeologist and Kent’s Cavern excavator William Pengelly (above) on ‘The submerged forests of Torbay’ tells us, “A few years ago Mr CE Parker purchased an elephant’s tooth off some Brixham fishermen who had just taken it up in their trawl whilst fishing in Torbay”. This was found to have come from an extinct mammoth, further proving that the earth was very… very… old and challenging the time-line of the Bible.

Some of these relics can be seen in Torquay Museum – there are ancient axes, alongside the bones of wild boar, wolves and massive extinct wild cattle called aurochs, all found in Kings Garden. And, after severe storms, it’s even possible to view at Torre Abbey Sands, Goodrington and Broadsands, the exposed remains of a long-submerged forest, comprised of logs, roots and branches.

These are the remains of our antediluvian past, of around 5,000-10,000 years ago. After the last ice age ended, the world warmed and deer, aurochs, and wild boar headed northward and westward, and around 9,000 BC, hunters followed. This was the Mesolithic -or middle Stone Age – and people could make this journey as the sea level was 30 to 40 meters lower than it is now. At that time the British Isles and the European mainland formed a continuous landmass, crossed by great rivers. Indeed, if you walked far enough from you would be confronted by the Rhine, joined far upstream by the Thames, as it flowed east to west to reach the sea somewhere around Brittany.

This immense landmass has been named Doggerland after the Dogger Bank, which in turn was named after seventeenth century Dutch fishing boats called doggers. Using seismic survey data, acquired mainly by oil companies drilling in the North Sea, we now have a digital model of 18,000 square miles of what Doggerland looked like before it was flooded. Unfortunately, this didn’t include the seabed off Devon but, nevertheless, we are now learning more about what these lost offshore lands were like and who lived there.

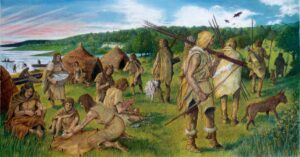

Archaeologists and anthropologists tell us there were fertile meadows and forests through which hunter-gatherers roamed. Yet, due to the way they lived, the peoples of the Mesolithic have left very little behind. They were few in number, did not permanently settle in one place, and moved across the landscape in search of food in the form of nuts or berries or game. They didn’t farm or keep animals, although they may have had hunting dogs, made no great monuments, and mainly lived in shelters of branches covered with the skins of the animals they hunted.

Much of the evidence we do have of these vanished folk are from their various stone tools. The period is known for small flint implements called microliths which were used as barbs fitted into wooden spear heads for hunting animals and fish. Other heavy hand axes were used for chopping and slicing.

Another reason why we find so little evidence is that they often lived on the coastline to access the benefits of both sea and land. Throughout this time, the sea level was gradually rising, at some times by 2 centimetres per year, as water locked away in glaciers and ice sheets was melting. The hunter-gatherers were slowly being flooded out – they were witnesses to the engulfing and death of the forests. Here was a paradise lost as the waters rose.

Indicating how things were changing, archaeologists have recorded a shift in diet, from freshwater fish to marine species, as the sea rise transformed the land from inland lakes surrounded by game-filled forests, to reedy marshes and eventually to the open sea.

By around 6,000 years ago the shape of Torbay’s present coastline had been roughly established, The Mesolithic peoples had been forced away from their hunting grounds – some headed for France, while others ended up on the higher grounds of Torbay as the waters rose.

Eventually, from around 4,500 BC people would give up their hunter-gatherer lifestyle and become farmers. However, a diet based on a limited number of crops meant that people weren’t getting as wide a variety of nutrients as when they relied on a range of food sources. This often left them malnourished. Living in agricultural communities with a higher population density, disease-carrying animals, and poor sanitation, all helped diseases spread. People became sicker, their height decreased and their health worsened as they traded hunting and gathering for the garden and the herd. Torbay had lost its Arcadia.

Some say that this traumatic loss of Eden has fixed itself in the human memory – many cultures across the world have legends of great floods. Our Celtic contribution to this mythology is the legendary paradise of Lyonesse, supposedly sunken beneath the waves off the South West coast…