“Deep night, dark night, the silence of the night, spirits walk, and ghosts break up their graves”, William Shakespeare

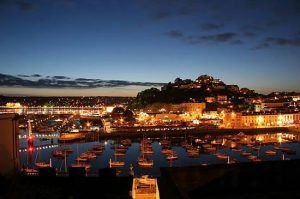

Night-time Torquay is another Torquay. Late at night, despite the electric light and the remnants of Harbourside nightlife, it can be unaccountably alien. Modern Torquay hardly knows pure darkness or silence any more, yet when the light fades ordinary sounds acquire sinister meanings and our roads echo with emptiness. The night creatures come out, our town’s bestiary – nocturnal gulls flying the Fleet Street canyon pillage Kentucky scraps, rats rustle in bins, foxes slope away, and the occasional badger can be seen even at Castle Circus.

Some Torquay folk are more visible at night. These are our nocturnal workforce, the taxi drivers, delivery workers, cleaners and take away staff. Some are recently-arrived migrants performing the least popular forms of labour, and it’s at night that Torquay most closely resembles the ethnic mix of our cities.

The other wakeful denizens of the dark are those without a home to go to. The homeless experience of searching for shelter in the lanes and churchyards of Castle Circus, Ellacombe and Torre, subdued by alcohol and narcotics, hasn’t changed much since the eighteenth century. History surely moves at a far slower place for the homeless. Though we may try to understand their alienation, tragically we can still find them alien.

We’ve forgotten that our town centre and suburbs are built upon real earth, a prehistoric landscape. Under the depopulated roads and pavements are seven hills, the fast flowing Fleet lies buried beneath Primark, and Torre Abbey Meadows caps reclaimed marshland. At night everything seems made from the same monochromatic substance and there’s something surreal about those limestone cliffs and the blackness at the edge of the palm-lined promenade.

After midnight it’s difficult to resist the feeling that people walking alone are up to no good. We unfairly label them the mad, the bad, the lost and the lonely – those running out of time or with time to waste. It’s mutual suspicion, of course, and in these small hours it’s worth reminding yourself that the silhouettes of other wanderers can feel just as threatened by your presence as you are of theirs.

This isn’t new. For hundreds of years anti social crimes were believed to take place after the coming of darkness. From the birth of Torquay in the early nineteenth century church leaders saw work as a duty to God, and at dusk the laborious and happy were expected to sink to rest. Meanwhile, those out after dark without a legitimate purpose were suspected of being immoral. Male nightwalkers were identified with disorderly drinking and criminality, or of experiencing the mania and insomnia associated with the opium so available on Torquay’s streets. Meanwhile, lone women at night were assumed to be prostitutes – one in twelve Victorian women sold sexual favours. Street prostitutes were regarded as the most corrupt and disreputable and most middle class men were contemptuous of them – even if they used their services. Being uneducated and illiterate ‘streetwalkers’ left no memoirs and are the forgotten women of our town.

As Torquay grew, immigration from the countryside filled the poorly built buildings of the densely populated Pimlico and Swan Street. With almost no illumination these alleys were disease-ridden and known for the stench of animal and human waste. Gin – Torquay’s methamphetamine of the time – offered speedy but temporary relief from the anxieties of poverty, hunger and abuse at the end of a long working day. After cholera came to Torquay in 1849 we buried the open sewer that was the River Fleet, but not before the disease claimed the lives of 66 people in six weeks. Many of the dead were buried in Cholera Corner in Torre’s St. Saviour’s churchyard, the graves unmarked as the victim’s families lacked the funds for memorial stones.

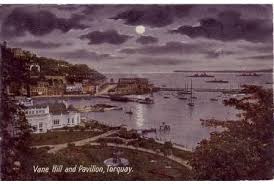

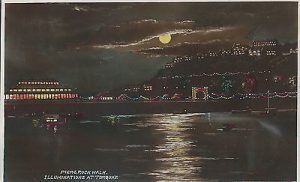

In the early years of Torquay, lanterns and candlelight were the sole sources of illumination but on October 8th 1834 the darkness was banished. Forty gas lamps were installed in our main thoroughfares – two years later the light extended from Castle Circus to Torre. This was modernity and it transformed the town. The richer classes could then act as both spectators and performers as they paraded Fleet Street and the Harbourside. This revolution inspired a local poet to write at the time:

“Come quick, Jemima, bring your shawl,

Come, come and take my hand,

And let us see the brilliant gas,

Just lighted on the Strand.”

Yet illumination was the privilege of the upper and middle classes while the poor, uneducated and illiterate inhabited a different social world. Indeed, while street lighting gentrified the commercial centre of Torquay, and allowed for ostentatious acts of consumption, it relegated other areas. The intense pools of light emphasised the darkness beyond and the dangers it concealed:

“Oh! And may it prosper, may it show,

The ruffian as he lurks,

And may the new light drive away,

The Devil and his works.”

There was always this parallel to the Enlightenment, and to a Torquay that wanted to portray itself as educated and sophisticated. Despite the triumph of the rational and scientific, the night remained a time when the findings of logic loosened, and a repressed and secretive Torquay surfaced. Despite the best efforts of the Church local people continued to believe in the power of witches. When a Watcombe house was being renovated in the 1970s, for example, a mummified cat was found behind the fireplace – the animal placed there to protect the inhabitants from evil spirits. Though fear of sorcery receded as medicine and education provided other explanations and cures, as late as 1875 local magistrates could still receive an application by a poor old woman in Chelston who believed that her husband had perished through witchcraft.

And Satan, the great enemy of humanity, continued to lurk in our imaginations. Legend had it that he lived in the caves beneath Daddyhole Plain – Daddy being the old English for Devil – and late at night he would emerge to claim his victims. In February 1855 panic ensued when the Devil’s supposed cloven footprints were found in overnight snow in Barton.

Once the richest town in England, Torquay has always been fascinated by the occult. From our very beginnings as a town we set up secret societies to explore hidden knowledge. Though now primarily philanthropic organisations, Torquay’s Freemasons (founded in 1810), the Oddfellows (1856), and the Foresters (1858) all claimed to have their roots in antiquity – in ancient Egypt, Rome or Anglo-Saxon Britain. They also used night rituals that so concerned the established Church.

This other side to the daylight of the rational was darkly reflected by an outpouring of literature exploring the uncanny, with many of the great writers on the macabre and mysterious having associations with our town. Mary Shelley (Frankenstein); Robert Louis Stevenson (Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde); Edward Bulwer-Lytton (The Haunters and the Haunted); Charles Dickens (A Christmas Carol); Arthur Conan Doyle (Sherlock Holmes); TS Eliot (The Waste Land); Rudyard Kipling (Tales of Horror); Oscar Wilde (Dorian Gray); Wilkie Collins (The Woman in White); Henry James (The Figure in the Carpet); Trevor Ravenscroft (The Spear of Destiny); Brian Lumley (Necroscope): all lived in or visited Torquay.

Yet there was always enough real horror in Torquay without the need for make believe. Secrets could be hidden after dark: Charlotte Winsor’s serial murder of babies in her lonely cottage at Lawe’s Bridge in 1865; the starvation which triggered riots; the exploitation of thousands in domestic service. We used to send the mentally ill and ‘idiots’ to be deliberately degraded in Newton Abbot’s workhouse – it wasn’t until the Lunacy Act of 1845 that the mentally ill were for the first time classified as persons of unsound mind. Out of the sight of the tourists; out of mind.

We’ve left behind our memory of the killing field of Gallows Gate where the ground is enriched by the remains of brutalised bodies of those convicted of trifling crimes against property. Our long and cruel tradition of criminal justice was reinforced by the Black Act of 1723 which imposed the death penalty for some fifty criminal offences. Thousands died from strangulation rather than a broken neck and were left to rot on the gibbet placed there for all to see – and now forgotten except by those of us with a grisly interest in such things.

And, of course, the night is the domain of the Torquay ghost, both ancient and modern. We were never short of supernatural visitations in our town – possibly one reason why more people still believe in ghosts in Torquay than anywhere else in the country. Among many other apparitions we have: Torre Abbey’s Spanish Lady; the Shrieking Nun of Ilsham Grange; Daddyhole’s Matilda; the hermit’s spectre of St Michael’s Chapel; and the White Ghost of Barton Hall. These stories acted to steer the unwary away from dangerous places – Kent’s Cavern had its malicious pixies – and dangerous people, such as the smugglers who worked at night. Spectres were entertaining and exciting, so we may have to look to those Victorian tourist guides who were known to invent or import exciting stories to enhance their income. The tradition continues through inventive modern promoters of attractions as they manufacture the macabre, as in the instance of Torquay Museum’s risen immature mummy.

In time our educated elite exchanged ghostly infestations for the more ‘scientific’ explorations of the supernatural in the form of animal magnetism, telepathy and Spiritualism – the latter a blend of parlour game, entertainment and new religion. In 1917 the Spiritualist Violet Tweedale explored the Warberries’ long-haunted ‘Castel-a-Mare’ where one of her investigators was quickly possessed and had to be exorcised. This savage spirit once more went on the offensive a few years later when the writer Beverley Nichols visited. He found that something, “black, silent and man-shaped rushed from the room and knocked him to the floor.” This was a violent poltergeist for a brutal time when the damaged and shell-shocked, returned from the trenches, could be seen roaming Torquay’s streets after dark.

Even the darkest night comes to an end, of course. So must all dreams and nightmares vanish with the first streaks of dawn over the Bay. But what we should always bear in mind is that Torquay’s night is far more than just a darker form of our day.