Hewn from local limestone and sandstone, secured to the crest of a lonely outcrop, St Michael’s Chapel has overseen and paralleled the evolution of Torquay; a Saxon hamlet, a rich and powerful Abbey, a Victorian resort, and now an urban conurbation. An enigma then; an enigma still.

Finding the Chapel

St Michael’s Chapel is to be found along the side of the Newton Road, in the woods right at the summit of the sheer limestone tor of Chapel Hill. You can glimpse it opposite Torre Station as you drive out of Torquay, past the Police Station heading towards Newton Abbot. If you want to visit from the Newton Road, drive up Old Woods Hill, turn right at the roundabout and there is some free parking outside Torre Primary School. A narrow path saves climbing much of the hill. But do watch where you step. The ghost is harmless, but this is dog walking country!

If you want to visit from the Newton Road, drive up Old Woods Hill, turn right at the roundabout and there is some free parking outside Torre Primary School. A narrow path saves climbing much of the hill. But do watch where you step. The ghost is harmless, but this is dog walking country! What you will find is a medieval chapel. It is probably thirteenth or fourteenth century, made from local grey limestone rubble with some red sandstone dressings, and is on the edge of a steep sided limestone cliff which may be a former quarry face.

What you will find is a medieval chapel. It is probably thirteenth or fourteenth century, made from local grey limestone rubble with some red sandstone dressings, and is on the edge of a steep sided limestone cliff which may be a former quarry face.

The hill was once tree-less and visible from the Bay. On his tour in 1783 the Reverend John Swete drew the chapel as being on a barren hillside.

It is a single space, with a slit window on the south side, along with an arched doorway and the stub walls of a former porch. The east end has an unglazed window opening. The west end wall is thicker towards the bottom with a slit window in the gable end wall.

There are traces of original wall plaster with a niche in the south wall which may have been a piscina, a stone basin for water used in the Mass.

The Mysteries

We don’t know what the Chapel was originally called, who built it, and why someone went to the effort and expense in the first place.

Unlike other chapels for which we have good records, little information on St Michael’s is to be found. While most historians assume that the chapel belonged to Torre Abbey, it is a bit strange that Episcopal registers and cartularies don’t record or even mention its existence.  There’s a question over whether St Michael’s Chapel should be known by that name. Unarguably the title is fitting. St Michael is a saint of high places, and there are several other St Michael’s built on steep hills such as Brent Tor, in Cornwall, and the famous example in Normandy. Yet, in 1616 John Speed called it St Marie’s Chapel as did an artist in an old map in 1662. One proposition is that Roger de Cockington built and dedicated the chapel to his wife Maria.

There’s a question over whether St Michael’s Chapel should be known by that name. Unarguably the title is fitting. St Michael is a saint of high places, and there are several other St Michael’s built on steep hills such as Brent Tor, in Cornwall, and the famous example in Normandy. Yet, in 1616 John Speed called it St Marie’s Chapel as did an artist in an old map in 1662. One proposition is that Roger de Cockington built and dedicated the chapel to his wife Maria.

What was it for?

In the absence of any real evidence of function, a variety of suggestions have been made to why St Michael’s was built in the first place.

Over the years it has been described as: a sea mark; a light house; a place for lighting a warning fire beacon; the abode of a hermit; a place of retreat; a prison; or a votive chapel built by mariners who had escaped shipwreck. The lighthouse suggestion is questionable as Chapel Hill is a long way inland, while the cliffs of Waldon Hill would have been more visible for those at sea. On the other hand, that the chapel should have become associated with seafarers isn’t unusual as there is a strong link between ecclesiastical communities and the sea. Medieval monks and hermits did help shipwrecked sailors, build chapels to guide seafarers, and profit from salvaged goods.

The lighthouse suggestion is questionable as Chapel Hill is a long way inland, while the cliffs of Waldon Hill would have been more visible for those at sea. On the other hand, that the chapel should have become associated with seafarers isn’t unusual as there is a strong link between ecclesiastical communities and the sea. Medieval monks and hermits did help shipwrecked sailors, build chapels to guide seafarers, and profit from salvaged goods.

Religious hermits lived on their own to escape the temptations of the world and usually fled far from human habitation. It doesn’t make much sense to live in isolation only a mile from the richest Premonstratensian abbey in England.  Chapels are not uncommon. Around 4,000 parochial chapels were built between the twelfth and seventeenth centuries. These were usually places of worship for parishioners who lived at a distance from the main parish church; or they were built for private worship by wealthy families. Yet nearby is the medieval, and more accessible, St Saviour’s at Torre while the Abbey could even be seen from the site.

Chapels are not uncommon. Around 4,000 parochial chapels were built between the twelfth and seventeenth centuries. These were usually places of worship for parishioners who lived at a distance from the main parish church; or they were built for private worship by wealthy families. Yet nearby is the medieval, and more accessible, St Saviour’s at Torre while the Abbey could even be seen from the site.

Therefore, we need to look for another purpose for St Michael’s.

What gives us a clue is the floor of irregular bedrock. A lot of time, money and effort was put into the chapel’s construction, but no attempt has been made to level the rock inside the building. It is very uneven and falls away from east to west, and has never been sealed by a stone, tile or wooden floor covering. However, this rock floor shows considerable signs of wear near the entrance, suggesting heavy use over many years.

This uneven floor, alongside the setting on the limestone summit, indicates that the chapel may have been built to mark and enclose a sacred space. The conjecture is that it was constructed on the site of a religious vision and so became a place of pilgrimage.

Another suggestion is that it is the site of an older place of pre-Christian significance. It was common to build churches on former pagan sites and the Archangel Michael was the field commander of the Army of God in the Books of Daniel, Jude and Revelation. St Michael led God’s armies against Satan’s forces during his uprising. In this view, Torre’s early Christians acquired the site for their new religion, proclaiming dominion over evil, with the chapel, whatever its true name, coming later. As for a date, the nearby St Petrox Well, where Andrew’s Church now stands, has possibly been used by Christians from the sixth century. These two explanations, of a vision and of a symbolic victory, are not mutually exclusive. We also recognise that the uses of the building will have evolved over the centuries.

The Tunnel to the Abbey

Occupying the interstices between what we do know as factual about the Chapel come fables and allegories. Hence, the claim that a secret tunnel connects Torre Abbey with the Chapel.

The obvious question we need to ask concerns the real logistical challenge of digging a tunnel over half a mile long, and then a vertical shaft through the centre of a limestone outcrop, for no discernible reason.

But perhaps the existence of the tunnel isn’t as important as to why people thought that it may actually really be there.

These claims about the existence of hidden tunnels often involve improbably long subterranean passages, sometimes running under major obstacles such as rivers and lakes to reach their destinations.  There are many examples, in particular, of secret tunnels associated with abbeys across the country. What they appear to have in common is the Reformation and the suppression of the Catholic Church. It was in 1539 that the white-robed canons of Torre Abbey surrendered to Henry VIII’s commissioner at the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Beginning from the reign of Elizabeth I, Catholic priests used these hidden rooms called priest holes to escape Protestant persecution. Catholicism was forced metaphorically underground and, in the case of priest-holes, by necessity hidden away from view.

There are many examples, in particular, of secret tunnels associated with abbeys across the country. What they appear to have in common is the Reformation and the suppression of the Catholic Church. It was in 1539 that the white-robed canons of Torre Abbey surrendered to Henry VIII’s commissioner at the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Beginning from the reign of Elizabeth I, Catholic priests used these hidden rooms called priest holes to escape Protestant persecution. Catholicism was forced metaphorically underground and, in the case of priest-holes, by necessity hidden away from view. Reinforcing community anxieties during the post-Reformation period, a number of monastic sites were purchased by Catholic families, as was Torre Abbey by former recusants the Carys. So, there may have been a legacy of local mistrust of Catholics generally and a suspicion that ‘Romish’ activities were carrying on ‘beneath’.

Reinforcing community anxieties during the post-Reformation period, a number of monastic sites were purchased by Catholic families, as was Torre Abbey by former recusants the Carys. So, there may have been a legacy of local mistrust of Catholics generally and a suspicion that ‘Romish’ activities were carrying on ‘beneath’. The other possible cause of such a local interest in hidden tunnels is the link to smuggling. Free traders avoided the excise man by making use of drains, sewers or water supply conduits, and in a few cases constructed tunnels. And around the Abbey there were the remains of extensive underground drains and water channels to be found.

The other possible cause of such a local interest in hidden tunnels is the link to smuggling. Free traders avoided the excise man by making use of drains, sewers or water supply conduits, and in a few cases constructed tunnels. And around the Abbey there were the remains of extensive underground drains and water channels to be found.

So it doesn’t appear that there is a passageway beneath Chapel Hill. Yet, there very nearly was. The original plan for the Newton Abbot to Torquay railway called for a tunnel right through Chapel Hill.

The Secret Chapel

The tradition was that the Protestant Reformation had at its core a general rejection of Roman Catholicism with the population welcoming religious reforms and the closing of institutions such as the Abbey.

The alternative view is of Henry’s elite-led revolution being imposed on a community devoted to the old ways.

What we do know is that across Devon instructions from Parliament and Lambeth Palace were often quietly ignored and churches continued to use Catholic ritual long after the 1534 rupture with Rome. A strengthening state, however, began to be more insistent on change and in 1547 the Protestant Edward VI came to the throne spurred on by evangelical advisers determined to eradicate any remnants of Catholicism. Injunctions stripped out the fabric of Catholic life in local churches so valued by local communities, with many statues and shrines smashed or removed. In 1549 the Act of Uniformity replaced the Latin liturgy with Archbishop Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer triggering widespread unrest. The peasants of Cornwall and Devon rebelled, and a volunteer army marched eastward, capturing castles, destroying enclosures and laying siege to Exeter. Using foreign mercenaries, this Prayer Book revolt was crushed, and 5,000 poorly armed rebels were slaughtered. We aren’t aware if Torbay was represented in the rebel dead, but it is very possible that they were. Local folk would have at least sympathised with the rebellion.

Injunctions stripped out the fabric of Catholic life in local churches so valued by local communities, with many statues and shrines smashed or removed. In 1549 the Act of Uniformity replaced the Latin liturgy with Archbishop Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer triggering widespread unrest. The peasants of Cornwall and Devon rebelled, and a volunteer army marched eastward, capturing castles, destroying enclosures and laying siege to Exeter. Using foreign mercenaries, this Prayer Book revolt was crushed, and 5,000 poorly armed rebels were slaughtered. We aren’t aware if Torbay was represented in the rebel dead, but it is very possible that they were. Local folk would have at least sympathised with the rebellion. From then on Catholicism was suppressed. Religious toleration of the Old Faith, alongside Protestant Nonconformism, was only granted in 1828.

From then on Catholicism was suppressed. Religious toleration of the Old Faith, alongside Protestant Nonconformism, was only granted in 1828.

A 1793 guidebook, nonetheless, reports that, “The Tor Chapel, perched on the summit of the ridge of rocks, once an appendage of the abbey before us and as it has not been desecrated it is sometimes visited by Roman Catholic crews of the ships lying in the bay.” Does this suggest some survival of old traditions in the Bay, and that some local folk still recognised the Chapel as a sacred space?

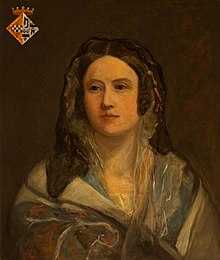

During the first half of the nineteenth century Torquay saw a significant rise in the numbers of Catholics, largely due to an influx of people from other parts of Britain. Seemingly acknowledging the importance of the Chapel in a long Catholic tradition, the philanthropist Sophia Crichton-Stuart, Marchioness of Bute (1809-1859), had a cross placed on the roof of St Michael’s Chapel. That cross was made from Bath Stone, the limestone that gives Bath its distinctive appearance.

Seemingly acknowledging the importance of the Chapel in a long Catholic tradition, the philanthropist Sophia Crichton-Stuart, Marchioness of Bute (1809-1859), had a cross placed on the roof of St Michael’s Chapel. That cross was made from Bath Stone, the limestone that gives Bath its distinctive appearance.  Her son was the richest man in Britain, the third Marquis of Bute (1847-1900) and his summer residence was Bute Court, now Belgrave Road’s Marquis Hotel. The influence of the family in Torquay can also be seen in the ancestral home of the Butes, Scotland’s Mount Stuart House.

Her son was the richest man in Britain, the third Marquis of Bute (1847-1900) and his summer residence was Bute Court, now Belgrave Road’s Marquis Hotel. The influence of the family in Torquay can also be seen in the ancestral home of the Butes, Scotland’s Mount Stuart House. The cross erected by his mother remained on the Chapel until 2015 and was then taken down and ‘lost’. It was declared to be anachronistic and incongruous, just a frivolous Victorian imposition on a medieval chapel. Though perhaps it signified and commemorated something important in Torquay’s history.

The cross erected by his mother remained on the Chapel until 2015 and was then taken down and ‘lost’. It was declared to be anachronistic and incongruous, just a frivolous Victorian imposition on a medieval chapel. Though perhaps it signified and commemorated something important in Torquay’s history.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon