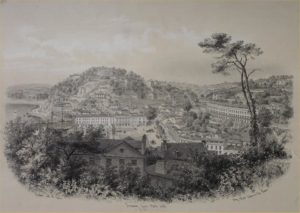

In 1800 Torquay had a population of only 800.

Before the arrival of Royal Navy officers and their families, the consumptives seeking a cure, and the Victorian tourist, Torquay consisted of a scattering of rural communities.

But by 1851 the town had 11,474 residents with many working classes folk having been drawn in by the expectation of work. They brought with them their country traditions, to join with those practiced in our farms and hamlets for hundreds of years. What incoming folk found in Torquay was a capitalist society where relationships were to be negotiated and understood only in hard cash. Consequently, these old ways often weren’t appreciated by the town’s sophisticated elite and they either fell into disuse or were suppressed as Torquay ‘matured’.

Today some of those traditions may seem a bit ‘Wicker Man’, but they held the unwritten history of our people. Here were important ideas about community, and a different, more fundamental concept of the calendar to that imposed in nineteenth century Torbay – traditions rooted in nature, survival and companionship.

Torquay’s new working classes quickly adopted an Easter festival which had been around during the time of Torre Abbey’s medieval Abbots – in 1867 it was reported that, “On Easter Monday Lower Union Street was obstructed by stalls and swinging boats were in great request. On Tuesday Torre Square and East Street were blocked up with swing-boats, caravans, shows and sweet stalls.”

One feature was the election of a Lord of Misrule, possibly a pagan survival. “At Torre the young fellows elected one of their order as Lord Mayor, and chaired him through the town, levying contributions at every public house, after which they visited Torre Abbey, where they never failed to receive a hospitable reception. The day’s perambulation invariably concluded by depositing the civic dignitary in the horse-pond at the bottom of the Avenues.” Note the symbolic ending of the Lord’s rule.

However, this couldn’t go on in a place which based itself on hierarchy, order and deference. “At length the disorders to which the fair gave rise compelled the Local Board of Health to take decisive measures. And they accordingly directed the police to prevent the thoroughfares from being disrupted. So the fairs were extinguished.”

Other Torquay rural traditions weren’t taken seriously. So we are fortunate to have a report entitled ‘Relics of the Past observed at Torquay, Devonshire’ (1873) by William Pengelly, geologist, archaeologist and excavator of Kent’s Cavern.

William (pictured above) writes, “I have occasionally regretted that the extension of the Railway system is so rapidly hunting down, killing, and burying the Past”. So he took the,” opportunity of recording, a few relics of the past which I have observed at Torquay”.

One recollection of William was a visit on Christmas Eve, 1836, to the old Torwood Manor House (pictured above), then occupied by John Madge. A ceremonial ‘ashen faggot’ was prepared and burnt. “It was made in the farm yard, and bound together with as many ‘binds’ of withe as could be well put on it” and “drawn to the front door of the house by four oxen and taken thence and placed on the blazing hearth. All, however, were attentive to the fate of the binds, and as each was observed to give way a demand for a gallon of cider was made on the farmer, who promptly supplied it.”

William sadly relates, “At that time the custom was observed in all the principal farm houses of the district, but it appears to be now a thing of the past.”

Another annual event took place on the eve of Mayday. All the flower gardens in Torquay received “visits from a great number of young girls of the artisan and labouring class, who solicit ‘some flowers for the May-doll, sir.'” If they weren’t given the flowers, “they might be stolen during the following night”.

On May-day morning each girl, with “a thin box about eighteen inches long and covered neatly with a white napkin” visited every house, “or boldly stopping on the Queen’s highway the wayfarers she may chance to meet”. She then “drops a hasty curtsey”, and asks ‘Will you please to see a May-doll?’ and displays a prettily dressed doll lying on a bed of flowers.” In response the girl is rewarded with a coin. William believed that, “the Torquay May-dolls are a relic of the worship of Flora, which Christianity, though established in our island for so many centuries, has not utterly exterminated.”

They could also be a relic of feudal pre-Reformation mutual support between lord and tenant.

At around 10 pm on January 5th, 1849, William heard “repeated sounds of fire arms in the direction of the hamlet of Upton”.

On investigation he found “a ceremony, then annually performed in the neighbourhood, for the purpose of securing a plentiful crop of apples in the coming season.”

The Upton farmer and his labourers were in the orchards chanting in unison:

“I drink to thee

Old sour apple tree,

To bear and to blow

Apples enow;

This year, next year,

And the year after too;

Pocketfulls, hatfulls,

And Tor Abbey Great Barn Full!”

After which they discharged their fire-arms amongst the trees, and returned to the house. During their absence, however, the ladies, had locked the door, and only allowed the shooting party to enter for food and cider when one of them had guessed what was cooking on the fire.

This was wassailing, recorded across the cider-producing West (primarily Devon, Somerset, Dorset, Gloucestershire and Herefordshire). It may be much older as wassailing seems to have pagan connotations, but there’s no real evidence prior to the middle ages.

Again, with regret, William records “So far as I have been able to find, the ceremony is no longer observed near Torquay.”

Yet wassailing still carries on in rural Devon and closer to home in Cockington.

In Stoke Gabriel the wassailers do put a virgin in a tree at one point- another possible reason why we don’t see the practice any more in urban Torquay: