A railway station serving Torquay was opened on 18 December 1848, but this station was far from the harbour at the centre of town. This wouldn’t do and a new station near Abbey Sands was opened on 2 August 1859 with the original station renamed “Torre”. Goods traffic continued to be handled at the original station while the new one focussed more on paying passengers, their horses and carriages.

A greatly improved station by the architect and engineers William Lancaster Owen and J.E. Danks was opened in September 1878 and the line, which had been a single track with a passing loop in the station, was doubled in 1882.

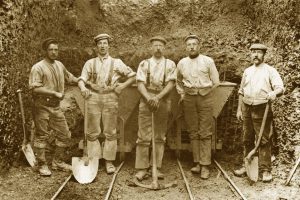

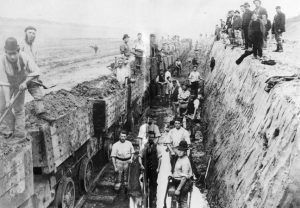

What we don’t hear much about are the people who actually built the railways. These were the navvies – shortened from ‘navigators’, the canal-builders of the eighteenth century. During the mid nineteenth century one in every 100 people who worked in this country was a navvy – 250,000 of them.

The building of railways was very labour intensive, the bulk of the thousands of miles of rail lines laid having to be done by hand and without the use of machinery. Navvies were hard men with their own code of honour, their standard tools were picks, shovels and a wheelbarrow. By the standards of the time, navvies were well paid, earning 25 pence a day which compared well to those who worked in factories. Yet, this was dangerous work. For each mile of rail laid, there was an average of 3 work related deaths, which was even higher when working on sections that required tunnelling. All work was done in a hurry and safety procedures were minimal – there were plenty of replacements eager for employment.

Navvies lived by the rail line that they were building in so-called shanty towns, in huts that could accommodate 20 men. They paid one and a half pennies for a bed for the night. Those who slept on the floor paid less – five nights of floor sleeping cost one penny.

We know most about the lives of navvies from hostile local newspapers who portray them as drunk, violent and unruly men. Their drinking was notorious and towns like Torquay feared their arrival. “Going on a randy” was navvy slang for going on a boozing spree that could last several days. These were men apart and navvies developed their own dialect as a means of communication among themselves. This was often rhyming slang which bonded the men together but it also left outsiders confused and excluded – as it was meant to. Not surprisingly this bred tension and distrust between locals and the navvies.

So during the 1840s Torquay had a large community of aggressive men with a liking for alcohol living in a shanty town at Torre, a group that had little fear of authority, speaking their own dialect, and with many from Catholic Ireland.

Yet, the potato blight that ravaged Ireland in the mid-1840s also affected Devon, leaving in its wake fields of withered plants. The crop was insufficient to meet the needs of those unable to afford any alternative to the potato for their staple diet. Two bad harvests also led to a dramatic rise in grain prices. In the first six months of 1847 prices paid for wheat at market doubled threatening to raise the price of bread beyond the reach of even working families.

Social unrest in Torquay increased and the authorities became increasingly alarmed. For example, in March 1847 a letter was found attached to the railing of the town’s courthouse. It read, “Whereas.- a grey headed Police-man, rather too busy in matters that did not concern him, So this is to give him notice, that some of his friends to prevent such vexation propose to administer a pill which dose will be delivery’d with a true hand. Signed by the following tradesmen and labourers. John Singleton, William Manners, George Weston, Thomas Ansty, Samuel Truman. Sworn to do their duty and not split. So take care of yourself.” This threatening letter was illustrated with “’pistols and a dagger in a heart copied from a Valentine’. The threat was taken seriously – “The terror excited amongst the Police is of course extreme.”

In May Bread Riots broke out across Devon. Dawlish, Okehampton, Cullompton, Crediton and Tiverton all saw disturbances. On May 17 a Torquay mob ransacked bakers’ shops in lower Union Street, “the contents of which were carried off by the women in their aprons’.

Several thousand rioters then raided shops in Fleet Street and Torre, and fought with local traders. A number were arrested, but the rioters demanded their release. It’s here that the navvies of Torre made their presence known. Some navvies had joined forces with rioting locals and been detained. From their encampment their comrades marched on the Town Hall to free them. 60 navvies armed themselves with “pick axes, crow bars and shovels, with the avowed purpose of pulling down the Town Hall”. The original Torquay Town Hall is opposite WH Smiths in Union Street.

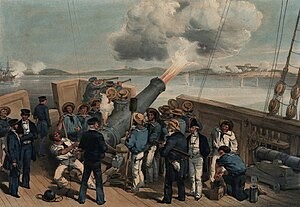

To restore order, a revenue cutter, the Adelaide, and a government steamer, the Vulcan, brought a detachment of coastguards. Forty troops arrived from Exeter while 300 special constables were sworn in. Eventually, 27 rioters were jailed. However, the prisoners had to be sent to Exeter by sea, instead of by road, as a plot to rescue them had been discovered.

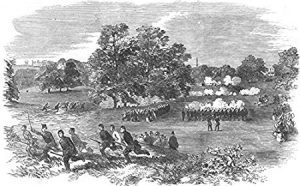

Alarmed by both local uprisings and foreign threats, in February 1853 a public meeting was held in the Town Hall. It was resolved to set up a company of volunteers and 80 men were armed and given uniforms. This display of force was designed to discourage further uprisings and would be most apparent in a Sham Fight between companies of Devon Volunteers that was held on Torre Abbey Meadows in July 1855 (pictured below).

Fear of the navvies continued, however. The majority of navvies in Britain were English, although the Irish comprised about 30% of the workforce. The railway-building boom of the 1840s had coincided with an agricultural crisis in Ireland, and navvying provided a means of subsistence that would otherwise have been lacking. Many Irish navvies sent their earnings home. Yet, having travelled to England seeking work, the Irish navvies were often treated with contempt. Religious differences were accentuated by the desperate Irish being prepared to work for less money, thereby lowering wages for other workers.

In 1867 there was a rebellion called the Fenian Rising against British rule in Ireland. Organised by the Irish Republican Brotherhood it failed but caused panic in England. In December 1867 “in consequence of Fenian agitators” a force of 300 special constables was raised in Torquay. Presumably this was to counter an assumed threat from those Irish navvies who were busy creating the Torquay that we know today.

Just so we don’t forget the real builders of our town, here’s a musical tribute to those hard working and hard drinking men:

For more local news and info, return to our homepage.

You can also join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon. Got a news story or press release that you’d like to share? Contact us

//pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/js/adsbygoogle.js

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});