So when and why did Torquay’s ‘Golden Age’ come to an end?

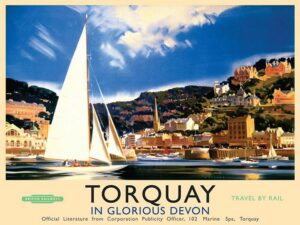

We begin with the nostalgia for the post-war holiday, reinforced by those railway advertisements describing the leisure and luxury that awaited in the Bay.

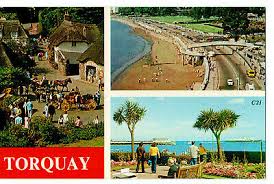

It may be that we now see the great vacation experience through rose-tinted glasses, yet from the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth, coastal towns like Torquay did form a halo around the edge of Britain. In 1949 five million holidaymakers visited these compact wonderlands with their infrastructure targeted at the influx of holiday makers desperate to spend their savings by the sea.

Of course, it wasn’t always a great experience as the Spectator Magazine’s James Pope Hennessy found in Torquay in 1947, “The whole town was swarming with holiday-makers, only they did not seem to be making holiday. There was something unduly oppressive in the empty, questing faces of the crowds that shuffled and shambled through the sunless, hot but steep and windy streets. They had nothing to do, it seemed, because there was nothing for them to do”. The post-war seaside holiday doesn’t sound that great with its crowded roads and trains, variable weather, poor food and grim guesthouses. On the other hand, we didn’t know any better… until the alternatives came along.

One suggestion is that the day everything changed was 5 May 1962 when the first flight of the new airline Euravia took off from Manchester, taking families on an all-inclusive holiday in Spain’s Palma de Mallorca. There had been package tours before, but rising wages and higher rates of employment presented the average family with a new type of holiday.

At the same time, the Beeching Axe was hacking away at the railways; the inexpensive trains that had long delivered holidaymakers from the cities were beginning to disappear.

From the early 1960s onwards, resort towns such as Torquay consequently faced a spiral of decline as the tourist base contracted and the clientele changed.

Social and economic change will always move more rapidly than the built environment, and this shift in the British vacation consequently left a legacy of the out-dated, rundown or just abandoned. While we can still see our history in our magnificent architecture, maintaining anything was a constant battle against sea gales. Without the promise of a good return, investment declined.

During the 1970s and 1980s Torquay was an unnoticed victim of a national transition that was taking place in the towns and cities that we served. For a time, the local economy was temporally boosted by high tech manufacturing, but changes in these sectors led to another wave of job losses and a further deterioration in confidence.

Lacking good employment, Torquay’s population changed as many ambitious young people left. In 2019 Healthwatch Torbay interviewed 2,000 local young people. Many believed they had no future in the Bay and expected to leave to find a good career. The diaspora of the talented young were being replaced by the affluent retired, an ageing demographic which added to the strain on social care budgets. The number of people aged over 85 In Torbay is expected to rise by 56% in the next decade.

Torquay once boasted 500 villas, many of which become hotels and boarding houses. With the decline in paying holiday-makers, those fine Victorian and Edwardian homes with sea views often became expensive apartments for incomers, while others were demolished or turned into care homes and cheap rental housing- often with absentee landlords. This drew in more economically vulnerable people, the urban homeless, those with physical and mental health issues, and ex-offenders. Poverty was both a cause and consequence of dependency on drugs and alcohol. Many residents were accordingly less able to contribute positively to the economy and we experienced ongoing cycles of deprivation.

Low wages and high unemployment pushed coastal communities such as Torquay to the top of the league table for bankruptcy and individual financial failure. Six of the ten local authorities with the highest rate of insolvency were on the coast – first was Blackpool, then Torbay. The Bay would then become one of the most deprived areas in England, with 25% of children living in poverty.

Torquay became a town polarised in terms of wealth, housing, age and degrees of aspiration. It reflected many other seaside towns which had a lower than average employment rate, seasonal unemployment, an above average share of working-age adults on benefits, and lower average earnings.

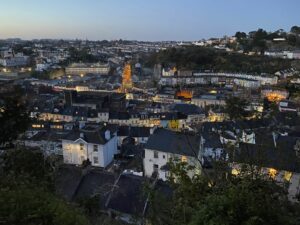

Eventually, the British seaside became, for the self-proclaimed intelligentsia, a national embarrassment. It would take decades, however, for some seaside towns to begin to resemble, for both locals and visitors, an inner-city by the sea.

On the other hand, it was often overlooked that all Britain’s towns faced challenges in the early twenty first century. Away from the town centre, Torquay took on the characteristics of any other provincial conurbation. Shopping relocated to out of town retail centres; consumer choice expanded hugely; increasing numbers of residents commuted to their place of work; many families and the retired achieved higher standards of living than ever before. All this was possible in a remarkably beautiful location.

And not all seaside resorts faced ongoing decline. Some thrived and have built a new economy on technology, ‘knowledge industries’, on higher education and health, and have made their towns attractive places for new businesses.

For a long time Torquay maintained its nostalgia for the old days with some developing a dearth of ambition and a recitation of regret. Maybe we needed a sudden trauma, as did the mining or steel-making parts of the country, to accept real change. Slow incremental lessening made it possible for tourism just to limp on, with some perhaps unable to let go and recognise that the future may be to diversify away from the town’s traditional industry.

Rather than nostalgia being a curse, it can also act to motivate regeneration and renaissance. Torquay still is an attractive place to live and work. The seaside and coastal heritage are part of our country’s greatest assets displaying and a rich history and fine architectural achievements. Local activists have insisted that we can save those buildings so we can go on using them.

By definition we will always be marginalised as we are on the edge of the country, but that can similarly be an asset. Entrepreneurs and visionaries made Torquay what it is and we see growth in the cultural and creative economy. Technology, flexible self-employment and a healthier way of living can help us keep our youth. Covid has accelerated change and shown that poor transport links are no longer the challenge they once were.

Partnerships are being enabled across the statutory and voluntary sectors and between local employers. Sustainable, successful regeneration is achievable, and now more public money is flowing towards the shoreline with Torbay Council being successful in attracting major funding.

From humble beginnings in the later eighteenth century, Torquay became an artistic and cultural centre, the richest town in England, and an arena of new ideas and ways of living. We have reinvented ourselves more than once already…