There’s an idea in archaeology and history called a palimpsest.

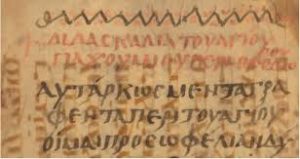

It comes from a parchment manuscript page. These were originally made of lamb, calf, or goat kid skin and were expensive, so they were often reused by scraping off any earlier writing. The enquiring eye can, however, read traces of all these erased writings. Archaeologists and historians now use the term to describe a landscape which has been erased and reused, worked upon for one purpose and later reused for another.

And so we come to Torbay – reused and worked upon time and time again. We’re also not just talking about the things we can see- the medieval and early modern amongst the concrete and tarmac – in our churches, thatched homes, the Abbey and even in a few pubs such as the Hole in the Wall and the Devon Arms.

We’re including people, their memories and, just in the past few years, our DNA. And always remember that all this history has a soundtrack- from the animal skin drumming of a Mesolithic camp in a forest clearing to the electronic beat in a Paignton night club.

Our story of human and pre-human occupation begins before there was a bay in Torbay- before there was an English Channel.

The earliest evidence of humans in Kent’s Cavern can be traced back to half a million years ago. During warmer periods the land became habitable and our ancestors could walk the land bridge from what is now France. The remains of our primeval forest hunting ground can still be seen after storms wash away the sands, and glimpsed in the hand axes occasionally trawled up fro the depths by Brixham fishermen. We shared this land with wolf and bear.

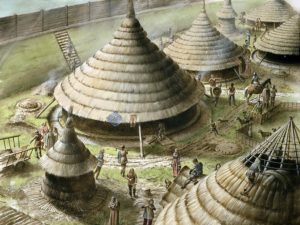

Our prehistory has mostly been wiped away by ploughing and development in an increasingly urban Bay, but some remnants can still be seen: on the Churston limestone plateau: in the Bronze Age field system on the cliff top at Walls Hill; in earthworks at Warberry Hill, Great Hill and Gallows Gate; and, at Milber Down and Berry Head. These are traces of the Bay’s original inhabitants who would become known as the Dumnonii people.

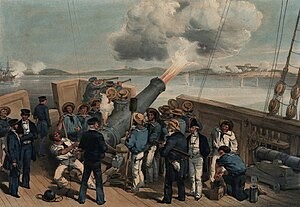

The Dumnonii were there when Romans established their fort in AD 55, at the southwest terminus of the Fosse Way. This served as the base for their 5,000-man Second Augustan Legion which dominated south Devon for 350 years. The Romans referred to this co-opted place as Isca Dumnoniorum, ‘Watertown of the Dumnonii’- we know it as Exeter. But perhaps – as the Kingskerswell excavations suggest – the Romans were always closer neighbours than we ever thought.

And the palimpsest can be seen in the names of places. Following the end of the Roman occupation in around 410AD, the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain began. From the mid-fifth to early seventh centuries this process of settlement changed the language and culture of most of what became England. These Germanic-speakers, themselves of diverse origins, eventually developed a common cultural identity as Anglo-Saxons and established kingdoms in the south and east of Britain, later followed by the rest of modern England.

Yet, it took a long time for Anglo Saxon raids westwards, beginning about 660, to end with a final conquest of Devon by Wessex under King Aethelstan. Certainly, the far South West remained ‘Celtic’ for much longer than other parts of England. Yet, it did fall – In 927 Aethelstan expelled what he called “that filthy race” of Britons from Exeter. In 936 there was a battle against King Howel of the West Welsh at Haldon Hill above Teignmouth where the Britons were finally routed. It was Athelstan who then fixed the boundary between the English and Cornish peoples at the bank of the River Tamar.

What happened to the Dumnonii after their defeat gives us another layer to the palimpsest.

Paignton is probably derived from ‘Paega’ which is an Anglo-Saxon personal name, with ‘ton’ a settlement. Paignton, therefore, appears to be a new Anglo-Saxon community – ‘Paega’s settlement’. On the other hand, it is thought that the designation ‘Brixham’ comes from Brioc’s farm -a Brythonic Celtic personal name. So, is Paignton originally Anglo-Saxon and Brixham originally Celtic? Such coexistence is supported by old records that show that the Celtic language was still being spoken in the South Hams in the Middle Ages.

Most Torbay place-names date from this settlement period. The term ‘ton’ refers to a settlement developed from an enclosed farm. Hence, Upton (upland farm); Cockington (the farm of Cocca’s people). Combe means’ in a valley’, so: Ellacombe (elder tree valley); and Babbacombe (Babba’s valley).

Yet original meanings are often forgotten. So as Tennyson stood atop Waldon Hill and the Sticklepath Fault that bisects Rock Walk – our very own San Andreas – to compose his poetry, he may not have known that its slopes hosted the vital food resource provided by the rabbit warrens for the Abbey. Hence, Warren Road.

It was the geology that shaped our modern Torquay. Limestone canyons were carved and quarried away by hand and blasting powder to be shifted a few miles to construct stolid and supposedly enduring Victorian villas. These stood alongside imposing local government structures with their aspirations to power and their faux marble features. Meanwhile, our other local construction resource of Devonian sandstone, with its propensity to crumble to its original state, caught some builders unawares. Perhaps they should have considered the erosion of natural features such as Corbyn Head. The eternal Geopark remoulds itself; we’re usually just not around long enough to really notice.

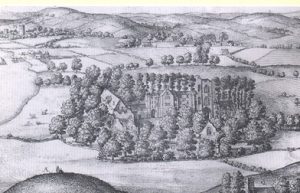

Residents’ world views further shaped the town. Development would come from discrete Victorian rivalry – a polite society competition, fortified by their Catholic and Protestant beliefs, between the Carys and Palks. The question: to adapt and modernise, such as at the despoiled Abbey, or to level and begin again… and again?

And we reshaped the land and changed its names to appeal to our new incomers – welcome this time as they came bearing gifts.

In 1877 the medieval Rotten Row causeway that traversed the Abbey’s tidal marshes was remade as Kings Drive. Beside this new thoroughfare was an embarrassing first view of Torquay as visitors disembarked from their trains. This was ‘Donkeyland’, “a receptacle for all manner of rubbish ‘mid which grew rank thistles to feed a fat and supine ass.” Running through Donkeyland was the Scire Brook, “a turbid stream meandering along this bestrewn channel and all around were evidences of depressing neglect”. The stream was diverted and on April 19th 1904 the ornamental ponds were formally opened. Even those familiar avian residents we love so much came to play a role to play in this new Torbay – at that prestigious opening Councillor WH Mortimer presented a pair of swans, the regal avian taking the place of the plebeian ass.

So that embarrassing and insignificant Scire came to feed a place of display and leisure. Yet the humble stream itself was ancient in its own right. It originated in a place called Scirewell, from the Old English scír – a clear spring – which we now know as Sherwell. The name betrays its primordial origins – a ‘scírwylla’ or clear well occurs in a charter by Offa in 785AD.

Names were always imposed by our elite, but locals would give their own to describe what they saw – in 1928 land was purchased for the sum of £4,000 from Devon Rosery and Fruit Farm Ltd. This new place of leisure was officially known as Sherwell Park, but it quickly became known as Pretty Park in the vernacular.

And so came a time when Torquay was the richest town in England. This left with a plethora of large Victorian and Edwardian houses. Within living memory those with sea and country views were replaced or converted into luxury apartments, while some without views became our Houses in Multiple Occupation.

But if we return to our theme of the palimpsest we find that the real evidence of palimpsest weren’t so obvious. That’s because they were hidden inside of us all the time. In 2015 research found that some Devon folk still retain a Celtic presence in our DNA – 1500 years after the Anglo-Saxon invasion. In this UK wide genetic test it was discovered that there remain separate genetic groups in Cornwall and Devon to the rest of Southern England, suggesting that the Anglo-Saxon migration into Devon was limited rather than any mass movement of exterminating Saxons.

The original Britons just seem to have gone ‘underground’. And, amongst the old names and new, the shaped limestone and the quarried sandstone, they’re still out there in Brixham, Paignton and Torquay. Beneath the Primark T-shirt there beats the heart of a tattooed and torqued Celt.

And so we can still visualise them all: the hominid; the Neanderthal; the Beaker folk; the Dumnonii; the Roman , the Saxon; the white-robed abbot; the Victorian consumptive; the Edwardian day tripper; the Beatnik; the Brummie, Scouser and Scot; the Pole and the Turk. Our Torbay homeland reaches from the Broadsands’ Neolithic to the Chelston nouveau.

From Factory Row to Marine Drive, our towns embrace wave after wave of incomer. And still they come to add yet another layer to the Torbay palimpsest.

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us