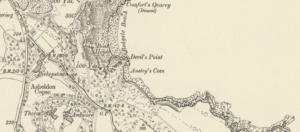

Anstey’s Cove is quiet, peaceful and beautiful, backed by limestone cliffs and a thickly wooded hillside. It seems to have first been recorded in a 1795 map as Anjus Cove and in 1827 as Anstie Cove.

Anstey is a common surname in the West Country and comes from the Old English word ánstíg meaning a narrow, steep track, possibly forking at both ends.

The Cove has a link with Agatha Christie. She enjoyed moonlight picnics there with her friends and supposedly once had a romantic liaison there with a chap by the name of Amyas Boston whose first name she later gave to one of the characters in her novel ‘Five Little Pigs’.

This is certainly an ancient place. Overlooking the beach is Walls Hill, the site of a prehistoric field system which dates from the Bronze Age (2000-700 BC) to the end of the fifth century AD.

But what we’re really interested in here is Devil’s Point, between Anstey’s Cove and Redgate Beach.

But what we’re really interested in here is Devil’s Point, between Anstey’s Cove and Redgate Beach.

There are many places across the world named after the Devil and these often owe their names to local geology, indicating a dangerous, extreme, or remote place. Interesting rock formations have always been associated with spirits, magic, strange phenomenon and death; with folklore adding tales of the eternal enemy of mankind.

There are 105 Devil’s Canyons in the United States alone, while imposing dangerous rocks known as Devil’s Peak can be found in Cape Town in South Africa, Hong Kong, Flanders Range in Australia, California, and in Nevada.

The Devil is also invoked in man-made structures. Locally the bridge near Chudleigh Knighton being one example; while Satan is often associated with prehistoric monuments. The Devil’s Arrows standing stones in North Yorkshire were supposedly thrown by the Devil as arrows in a failed attack on Christians in Aldborough.

Other references are less obvious.

Nearby we have Daddyhole Plain. Daddy is Old English for Devil’s Cave, caves often gaining a reputation of being deadly, a path to the underworld, or bottomless. In our local legend the foolhardy Matilda gives her soul away to the Devil in a revenge pact and is forever to be heard wailing her misfortune from the sea caves below the Plain.

Yet Devil’s Point in Anstey’s Cove does seem a little unimportant and obscure to have acquired such an emotive title. It doesn’t even seem to pose much of a threat to shipping, another reason used elsewhere for the name. Indeed, it would seem to make more sense to give that title to Long Quarry Point with its impressive and mysterious columns.

Could it be that Devil’s Point was the original name for Long Quarry and the name was transferred in order to avoid disturbing superstitious quarry workers?

Or perhaps there was some long-forgotten story attached?

There is a Devil’s Point in Plymouth. The story here is of a mysterious stranger tempting villagers with the offer that he could make the place the biggest port town in the region. The Devil – it was he – kept his part of the bargain and so we have Plymouth, while the villagers were turned to stone for their folly in believing the stranger. Even now, on occasion and only at the full moon, can you hear the cries of those villagers trapped in the rocks as they recount their regret at making an unfair bargain at Devil’s Point.

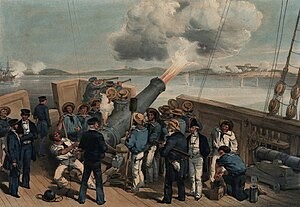

The other Plymouth Devil’s Point legend is of Sir Francis Drake (1540-1596), a figure long associated with witchcraft and diabolic pacts. Drake was rumored to be in league with the Devil and even to possess a magic mirror that allowed him to see the location of all the ships in the sea.

On one dark and stormy night, he was said to have entered into a deal with witches and demons on the headland, trading his soul for the storms that would destroy the Spanish Armada. Another story is of Drake playing bowls when the news of the Armada’s arrival prompted him to utter, “There’s time to finish the game and beat the Spaniards too.” He then sat on Devil’s Point whittling a stick and throwing the pieces into the water, each piece becoming a fully manned fire ship, ready to defeat the invaders.

We may well have simply borrowed the name of the Plymouth landmark.

We also have the tradition that wreckers would use the area to position lanterns as false lights to lure vessels onto the rocks of Oddicombe and Babbacombe. These would be hung on the horns of cattle, the idea being that ship capatinns would be led to believe that they were rounding Hope’s Nose into the shelter of Torquay and be wrecked on the rocks.

It is generally accepted, however, that such subterfuge simply would not work.

Mariners would always interpret any light as indicating land, and avoid them if they couldn’t definitely identify them. Also, ordinary oil lanterns cannot be seen very far over water at night. There have been hundreds of Admiralty court cases and no captain of a wrecked ship has ever reported to have been misled by a false light.

Wrecking by deliberately decoying ships on to the coast, despite being depicted in many stories and legends, therefore seems to a myth. There is no evidence that this has ever happened.

We do know, on the other hand, that South Devon’s smugglers were very active in the area. And it may be no coincidence that many local legends of malicious pixies, the Devil’s tricks and malevolent ghosts seem to originate between 1790 and 1820, a time when local smugglers were coming under increasing pressure from the Preventive Men.

Was the headland named as a way of keeping the curious away and explaining odd lights at night; or is there a much older story to be told about Devil’s Point?