During the latter years of the nineteenth century Torquay claimed to be the wealthiest town in all England.

Our mythical seven hills boasted five hundred villas where the prosperous middle classes had escaped the smoke of industry and the noise and dirt of urban humanity to reside in quiet residential areas.

Up to the 1840s Torquay’s town’s houses reflected Regency Classicism, but this simplicity fell out of favour as affluence increased. By the 1850s the Italianate style influenced architecture, while the Gothic Revival incorporated features such as pointed, projecting porches, bay windows, and grey slate. Large terraced houses, fashionable with the well off in the first half of the century, declined in popularity. They were replaced with detached or semi-detached villas with twelve rooms or more which offered more privacy and comfort.

Up to the 1840s Torquay’s town’s houses reflected Regency Classicism, but this simplicity fell out of favour as affluence increased. By the 1850s the Italianate style influenced architecture, while the Gothic Revival incorporated features such as pointed, projecting porches, bay windows, and grey slate. Large terraced houses, fashionable with the well off in the first half of the century, declined in popularity. They were replaced with detached or semi-detached villas with twelve rooms or more which offered more privacy and comfort.

These Victorian villas, catering for the middle classes and upwards, required accommodation for servants who were employed to carry out the considerable labour required to keep the house in order.

These Victorian villas, catering for the middle classes and upwards, required accommodation for servants who were employed to carry out the considerable labour required to keep the house in order.

Domestic service was consequently Britain’s biggest employer of 1.5 million people. As Torquay was primarily a leisure and health resort it needed an unusually large servile class which it pulled in from its surrounding villages. This saw women far outnumbering men.

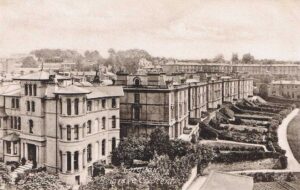

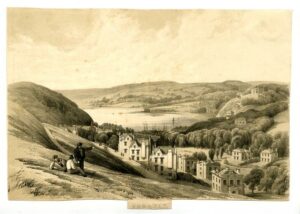

The site of The Imperial Hotel

In 1871 there were 12,772 females to 8,885 males in Torquay; by 1901 18.5 per cent of Torquay’s population were employed as domestic servants.

This gender imbalance was largely due to there being a tax on indoor male servants – men’s wages were considerably higher – and that women servants were regarded as being more obedient. In 1891 more than a million women – one in three women between the ages of fifteen and twenty – were in domestic service. The majority of them would have lived with their employer to attend to their every need, whatever the time of day.

Victorian households built up their staff of domestic servants in accordance with a well-understood pattern based on a progression from general functions to more specialized ones. Advice on this was given in literature on household management. In a very wealthy Torquay house there might be a dozen – such as that of Baroness Coutts of Ehrenberg House (pictured) where the ERICC Centre is now; and the long-gone Daison Villa.

Belgravia- off Belgrave Road

Domestic servants were divided into upper and lower classes. Yet, only a handful of households in Torquay were able to employ the whole range of recognised servant groups.

Indeed, employing staff was a sign of respectability, and even though new wealth had permeated down and led to a burgeoning middle class, many households could only afford a single servant. This was the maid of all work, often a young teenager working 14 to 16 hours daily at the most menial chores. If the family had a shop or ran one of Torquay’s boarding houses she would also serve behind the counter or cater for the needs of paying guests. The Victorian author Mrs Beeton, in The Book of Household Management, wrote that, “The general servant or maid of all work is perhaps the only one of her class deserving of commiseration. Her life is a solitary one and in some places her work is never done.”

Ehrenberg House now the ERICC Centre

Ehrenberg House now the ERICC Centre

As a family’s income rose, so would the number of its servants with a housemaid and cook being the priority. Wealthy visitors who came for the summer often brought with them a lady’s maid. Additional servants were engaged locally or even included with the property when they were ‘taken’ for the season.

In larger houses there was a distinct social hierarchy in the servants’ quarters. The senior servants had a great deal of power, and status was reinforced at mealtimes with a strict order of entering to eat, rules about where different ranks of servants sat, and no speaking unless addressed by one of the senior servants. Uniforms also maintained this ranking – the maid’s black dress, white apron and white cap was introduced to disguise personal identities.

For all servants this was a life of menial work, extremely long hours, meagre pay, and often harsh treatment by employers. For many this drudgery lasted from their early teenage years to well past middle-age. Some female staff, looking for additional income, or perhaps excitement outside of the domestic setting would offer sexual favours in return for small gifts. These women were known as ‘dolly mops’.

It was also a precarious living as staff could be dismissed immediately for breaking house rules or for displeasing the householder. Their ‘box’ of possessions may well be retained after dismissal and without possessions and a ‘character’ – a written reference – another position would be unlikely. In Torquay, without much in the way of industrial employment, the only other way of avoiding homelessness and starvation for dismissed women was prostitution.

Young maids on the lowest rung of that society were particularly vulnerable to sexual exploitation. Women in domestic service were further punished for giving birth outside of marriage. No woman could raise a child born outside marriage and remain in “polite society”, or employment, in the nineteenth century. They would often dispose of babies in privies or ditches, or resort to the local baby farmer and, if discovered, would be tried by male judges and jurors.

Young maids on the lowest rung of that society were particularly vulnerable to sexual exploitation. Women in domestic service were further punished for giving birth outside of marriage. No woman could raise a child born outside marriage and remain in “polite society”, or employment, in the nineteenth century. They would often dispose of babies in privies or ditches, or resort to the local baby farmer and, if discovered, would be tried by male judges and jurors.

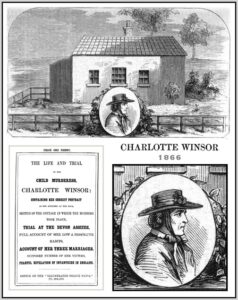

At Lowe’s Bridge on Torquay’s Newton Road lived the baby farmer Charlotte Winsor. On February 15, 1865, the body of Mary Jane Harris’ illegitimate four-month-old son was found beside the road wrapped up in a copy of the Western Times. Harris had farmed out the infant to Winsor for 3 shillings a week. At first she had resisted Winsor’s offer to dispose of the child though, when the burden of his support became too much, she stood by and watched Winsor smother her son. Testimony revealed that Charlotte Winser conducted a steady trade of boarding illegitimate children for a few shillings a week or “putting them away” – killing them – for a set fee of £5.

At Lowe’s Bridge on Torquay’s Newton Road lived the baby farmer Charlotte Winsor. On February 15, 1865, the body of Mary Jane Harris’ illegitimate four-month-old son was found beside the road wrapped up in a copy of the Western Times. Harris had farmed out the infant to Winsor for 3 shillings a week. At first she had resisted Winsor’s offer to dispose of the child though, when the burden of his support became too much, she stood by and watched Winsor smother her son. Testimony revealed that Charlotte Winser conducted a steady trade of boarding illegitimate children for a few shillings a week or “putting them away” – killing them – for a set fee of £5.

The domestic servants of Victorian Torquay are largely forgotten. They lived their lives anonymously. Few in wider society even recognised their existence at the time while the organised working class looked down on those in service as being subservient and unwilling to fight for their rights.

By the turn of the century, however, society was changing. While the population was expanding, the middle class growing and the demand for service also increasing, the supply of servants was shrinking. There were new opportunities in factories and shops where workers received better pay and even evenings and weekend off. In 1891, Britain’s indoor domestic servants numbered 1.38 million; by 1911 it had fallen to 1.27million .There were, however, fewer such alternatives in Torquay.

By the turn of the century, however, society was changing. While the population was expanding, the middle class growing and the demand for service also increasing, the supply of servants was shrinking. There were new opportunities in factories and shops where workers received better pay and even evenings and weekend off. In 1891, Britain’s indoor domestic servants numbered 1.38 million; by 1911 it had fallen to 1.27million .There were, however, fewer such alternatives in Torquay.

World War I had a profound effect. Men were sent off to fight and women came into traditional male working roles. After the War many women did not return to their domestic service roles and gradually the modern home of the middle classes was updated with new equipment to accommodate the shortage of servants – the introduction of flushing toilets, washing machines and electric ovens.

Over the years households became smaller, leaving Torquay with a legacy of large houses looking for a new role. Many of those surviving villas fortunate enough to have views became divided into luxury apartments, while others became small hotels, care homes or houses of multiple occupation. The rest is Torquay’s history…

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon