Many towns have an origin myth- a story that tells of how their community began.

The origin myth of Torquay was that our small rural communities were transformed by the families of Royal Navy officers who lodged their wives and families in this part of Torbay. This narrative is comforting and romantic, and still presented as a fact by the tourist industry. It is, however, questionable.

Torquay simply wasn’t big enough to cater for naval families during the Napoleonic Wars. The real focus for naval activity was Brixham, which in 1801 was the largest town in the Bay with 3,671 residents – Berry Head was the location of the Officers’ Hospital.

Paignton, with its population of 1,575, follows Brixham. A long way behind was Torquay with 838 folk; and the neighbouring St Marychurch with a close 801. Then there was Cockington with 294 souls. Significantly, unlike Brixham, there were no naval works in Torquay.

What gave rise to Torquay’s evolution from a collection of villages to the richest town in England was perhaps less glamorous. It was the decision to cater for the needs of the sick and dying.

‘The Guide to the Watering Places of South Devon’ (1817) states that the town “was built to accommodate invalids”. Octavian Blewitt’s ‘Panorama of Torquay’ (1832) confirms that, “houses were erected for the accommodation of the invalids”. Our climate was seen to be congenial to the sick and disabled, with varying levels and aspects being seen as suitable, according to a particular need.

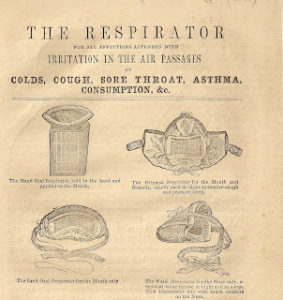

In 1840 Dr AB Granville visited Torquay and described our town. He wrote, “The Frying Pan along the Strand is filled with respirator-bearing people who look like muzzled ghosts, and ugly enough to frighten the younger people to death”. Torquay was, “the south west asylum for diseased lungs”.

The hotels were, “filled with spitting pots and echoing to the sounds of cavernous coughs, while outside the only sound to be heard was the frequent tolling of the funeral bell… awful and thrilling to the rest who were trembling on the verge of their grave with symptoms of the same devouring malady, Consumption”.

In 1838 alone there were 38 Torquay deaths from this disease.

Consumption was a common term for the wasting away of the body, particularly from pulmonary tuberculosis (TB), an infectious disease affecting the lungs. It was called ‘The White Death’ and before 1850 it was responsible for one in four deaths in England – until the 1870s it was the biggest killer of British people. The classic symptoms of TB were a chronic cough with blood-containing sputum, fever and night sweats. It was called ‘Consumption’ due to another obvious symptom- weight loss.

was such a focus for those with TB because so many came to be cured, to recover, and perhaps to stay in our consumption hospitals. Inevitably some didn’t regain their health and lie in the churchyard at Torre.

The respirators mentioned by observers were probably those of Julius Jeffreys (pictured above). In 1836 Julius offrered respirators, “constructed on scientific principles, and designed to facilitate respiration by supplying to the air passages and lungs, when in a delicate or irritable state, air fresh and pure, but rendered so genial as to be soothing to them, however cold, foggy, and irritating the atmosphere might be.” These were the prototype for respirators still manufactured today.

Although each health resort had long attracted large numbers of those seeking wellbeing, therapists disagreed on which climates were best suited to treating Consumption. However, in 1830, a Dr. Clark praised Torquay, claiming that the town, “possesses all the advantages of the South-Western climate in the highest degree” for the treatment of Consumption. And in 1831 the Irish surgeon James Johnson wrote a very successful book, ‘Change of Air, or the Diary of a Philosopher in Pursuit of Health and Recreation’, which recommended visiting health-giving resorts.

Medical and social perceptions of the disease then encouraged affluent patients to go for the ‘Change of Air’. In 1850, 90% of travelling British invalids suffered from Consumption and until the 1870s they dominated the peripatetic ailing community.

Initially TB wasn’t even seen negatively- it generated an income for the many hotels across town. And for centuries tuberculosis was associated with poets and artists and known as ‘the romantic disease’. Visitors to Torquay who suffered from the illness include Percy Bysshe Shelley, Robert Louis Stevenson, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Charles Kingsley.

Crucially, TB wasn’t seen as being infectious. It was understood to be hereditary. Even by the 1870s it was widely held that, though you didn’t actually inherit the disease, but rather a disposition toward it, it could be activated by environmental factors, including squalid living conditions and sinful indulgences.

Yet, this changed in the 1880s when TB was determined to be contagious and was put on a notifiable disease list. Consumption then quickly lost any glamour it may have once had and came to be seen as a threat to public health and decency. Public fears about infection, and telltale practices as coughing and spitting became both medical and social anathema. Campaigns then began to ‘encourage’ the infected poor to enter prison-like hospitals – in contrast, the sanatoria for the middle and upper classes offered good care and medical attention.

And in 1887 another health professional, Dr. Lindsay decided that Torquay had a climate, “too relaxing to be generally suitable for Consumption”. This was part of a general abandonment of seaside resorts for consumption therapy and a growing appreciation for mountain resorts, inland resorts, and the traditional sea voyage.

Nevertheless, the town retained its attraction for the sick and disabled. When the Canadian Isabella Cowen visited in 1892 she recorded in her diary, “Torquay, I have found, has an unusual amount of wealthy people. It also has a seeming monopoly of invalids. Some days I found the pleasure of our walks along Rock Walk and the sands perfectly destroyed by the number of infirm old people and still more lamentable, deathly looking young people who haunt that particular place of pleasure.”

In 1906 Albert Calmette and Camille Guerin achieved the first genuine success in immunization against tuberculosis. The BCG vaccine was first used on humans in 1921 in France and achieved widespread acceptance in the US, Great Britain, and Germany after World War Two. By then Torquay had long lost its association with the disease, but not with other health related issues. In 1930 Torquay was being recommended for, “Persons who have returned from the tropics”:

It had taken a century for Torquay’s tourist industry to collectively forget its origins in respirators, spitting pots and funeral bells; and to substitute a more picturesque creation myth comprised of the blue wool and mylar gold lace of the naval officer.

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon. Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon. Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us